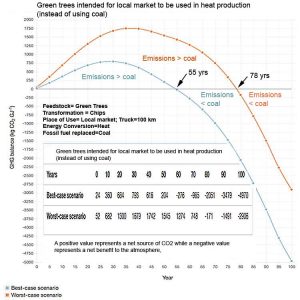

With 84% of area cuts being burnt via the Biomass Burner (73%) or Firewood (11%), PHP, NSP, NSDNR and even FSC are doing their part to increase GHG emissions while calling the practices “sustainable”.

** Regrettably, the Chronicle Herald apparently deleted a lot of its older online materials when it shifted to a new platform in Sep 2018, so this links leads to a “not available” notice. Some of the info is in this post:

VIDEO: Old-growth Crown hardwood being cut and burned, harvester says

AARON BESWICK THE CHRONICLE HERALD

Published February 23, 2018 – 5:00am

Last Updated February 23, 2018 – 8:38am

The two processors that had been cutting swaths through the hardwood stands on Loon Lake Road weren’t operating on Wednesday morning.

“They’re broke down — they’re not designed to be cutting hardwood this big,” said Danny George, a Guysborough County harvester.

“This area has never been cut. This is old growth.”

Taking a measuring tape out, one yellow birch had a circumference of three metres at the butt.

“Sure, they pick some saw logs out of it but primarily these trees are getting burnt for biomass,” said George.

That’s a big accusation on two counts.

The patches being cut out of the stands of mature hardwood have large trees, like this yellow birch with a circumference of just over three metres. (AARON BESWICK / Staff)

Because, according to the province’s Old Forest Policy, no one is allowed to cut old-growth forest on Crown land.

And, according to provincial government policy, Nova Scotia Power and Port Hawkesbury Paper, saw logs aren’t getting burnt for electricity at the Point Tupper mill.

We’ll start with the cutting of old-growth timber.

“The Old Forest Policy will conserve the remaining old-growth forests on public land and ensure that a network of the best old forest restoration opportunities is established,” reads the province’s policy document passed in 2012.

The document lays out a clear definition of old-growth forest:

•30 per cent of more of the total volume of wood in an area measured at breast height (known to foresters as the basal area) is composed of trees over 125 years old;

•At least half the area is taken up by climax species — long lived varieties of trees that require the shade of a forest canopy during their early years; and

•More than 30 per cent of the sky is blocked out by tree crowns.

“A hundred per cent it fits that definition,” said George.

“There’s at least 100 acres on the ground that hasn’t been processed that’s all old growth. There’s one stand by Rocky Lake that’s all ribboned to be cut that’s old growth that hasn’t been because both the processors are broke down.”

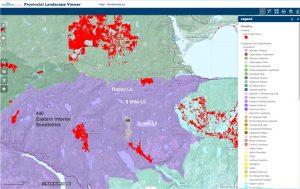

On Thursday, the Natural Resources Department provided an emailed response, stating that the majority of the 273-hectare harvest area between the Loon Lake Nature Reserve and Salmon River is primarily softwood and is not old growth.

“DNR has policies and procedures in place to ensure old-growth stands on Crown land are not harvested,” reads the response.

“All Crown land timber harvesting prescriptions are determined using forest management guides based on information collected during an on-the-ground pre-treatment assessment.”

Softwood stands of spruce and fir grow adjacent to hardwood stands primarily composed of large old yellow birch and sugar maple in the area between the Loon Lake Nature Reserve and Salmon River.

There are also areas where the stands are mixed.

George said while some of mixed stands being cut fall into a “grey area” as to whether they would qualify as old growth, he showed hardwood areas cut that he claims were composed of 85 per cent yellow birch and sugar maple.

Beyond the question of whether the area cut is old growth, there’s the question of what’s happening with the hardwood that’s being cut.

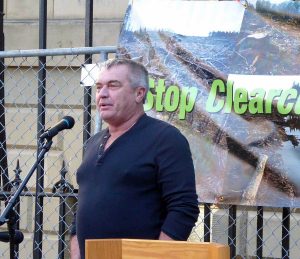

Guysborough County harvester Danny George is accusing the Department of Natural Resources of allowing old-growth hardwood to be cut and burned in Nova Scotia Power’s biomass boiler at Point Tupper. (AARON BESWICK / Staff)

“Good saw logs are being burnt (at the biomass boiler) and that’s a fact,” said Peter Christiano.

“They can say ‘oh there’s none going in (the boiler)’ but if you talk to any of the people buying logs, when they turn on that boiler, the supply goes way down.”

Christiano and his wife Candace founded Finewood Flooring in Middle River 33 years ago.

They and Rivers Bend Hardwood Flooring in Antigonish County shut their doors in 2015, citing a lack of access to hardwood from Crown land.

In 2012, the province signed management of the Crown land in northeastern mainland Nova Scotia and Cape Breton over to Port Hawkesbury Paper.

The 36-page Forest Utilization Licence Agreement gives the mill the right to harvest 400,000 tonnes of softwood and 175,000 tonnes of hardwood off the Crown lands it manages in the seven eastern counties.

It also demands that Port Hawkesbury Paper enter into agreements with hardwood producers in northern Nova Scotia.

All but one of those hardwood users has closed since the agreement was signed.

Groupe Savoie’s mill in Westville is the last operating hardwood mill in northern Nova Scotia and it’s only been sawing a day a week since Christmas.

“We’re in survival mode for the winter,” said Andrew Watters, manager of the mill.

“We need more logs.”

Watters, who does get some logs from Port Hawkesbury Paper and some from Northern Pulp, wouldn’t speculate on the cause of the shortage.

The shortage does coincide, however, with increased electricity production at the Point Tupper biomass boiler.

Since a change of provincial legislation in 2016, the facility, which produces very expensive electricity, only runs when it is economically feasible.

Nova Scotia Power confirmed Thursday that since October, cold weather, high natural gas prices and high electrical demand mean the boiler has been running a lot more.

“The fuel burned at the biomass plant is mostly from mill waste in the form of bark,” said Tiffany Chase, spokeswoman for Nova Scotia Power.

“At times, such as in the winter months, wood chips are used with the bark — typically 25 per cent of the biomass fuel. The chips can be either hardwood or softwood but are from lower quality wood that has no other commercial use.”

From its Crown allocations, Port Hawkesbury Paper cuts and chips the wood (predominantly hardwood) that is burned to supplement mill waste.

Mill manager Marc Dube said there is “no truth” to allegations good quality hardwood is being sent to the boiler.

He said the hardwood harvested on behalf of the mill is sorted to go to its most economical uses — some chips heading to Great Northern Timber in Sheet Harbour to be exported overseas, some going to Northern Pulp in Pictou County and top quality logs going to Group Savoie’s mill in Westville.

“It’s not a question of log supply, it’s a question of markets. Previously what they did to supply those (sawmills) is they high graded — they would go in and only cut high quality logs,” said Dube.

“As a result of that there’s no logs left for the (sawmills). The right approach to take in forest management is to follow the management strategies in place to manage for different forest types. We don’t clearcut shade-tolerant hardwood stands.”

Scott Cook’s family has run sawmills in Guysborough County since 1922.

He sold the mill in 2006 because he couldn’t get access to the hardwood all around him that the province had turned over to the paper mill’s former owners.

“My father couldn’t get access to Crown land and my grandfather couldn’t get access to Crown land,” said Cook.

“DNR gave me 10 acres in the 1980s and that’s all we’ve had since 1922. There’s 500,000 acres in this county. When the pulp mill came here (in the 1950s) there would have been about 250 sawmills in the seven eastern counties. There’s pretty well none left now.”

Three years ago Cook, who owns a mall and gas bar in Guysborough, went to the Guysborough County council and told them if they would lobby Natural Resources to allow him a Crown licence, he would buy a new sawmill and hire local people.

“We sent the letter,” said Barry Carroll, chief administrative officer for the Municipality of the District of Guysborough.

But the request was denied.

“We always felt we have this huge resource and it should first go to hardwood mills and be available for local use,” said Carroll.

An article in the March 2018 issue of

An article in the March 2018 issue of