Posted on Annapolis Royal & Area – Environment & Ecology Jan 23, 2021

PORCUPINE (Erethizon dorsatum)

Another natural history post — again, I’ll be jumping around with these — not just insects and spiders, but mammals, reptiles and amphibians, birds, plants — whatever. I enjoy writing about nature to share what I know. At this time of year, I can’t really be out wandering the woods too much, so this helps to pass the time.

I decided to write something about Porcupines after seeing three separate posts or photos by friends or on groups just this past couple of days, showing tree branches gnawed by Porcupines.

Seems like a good enough reason to post a few photos and say a few words about them.

As it happens, this is a very good time of the year to be thinking about Porcupines as they’ll often be seen up in trees, gnawing on bark and eating tasty leaf buds as nourishment to get through the last months of winter. If you remember to look up while hiking through the woods, you may well spot one far above the ground.

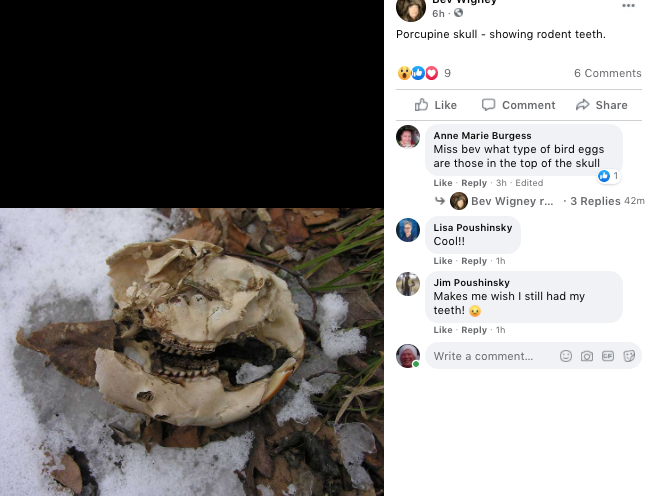

Porcupines are rodents — having paired incisors with which to bite and gnaw. They and Beaver are the largest of our North American rodents. In the photos, you’ll see one of the jaws of a Porcupine that Don and I came across while hiking in winter. I’ve also included a photo of a den that was dug into the side of rocky ledge, but I’ve found dens inside hollows of fallen trees, under the roots of large trees, and inside standing hollow trees. They are generally easy to spot by the amount of scat that is around the entrance — oval pellets that sort of look a bit like large alfalfa pellets. We once came upon a tree from which little cries were emanating. We peeked inside and there was a coal black baby Porcupine. We backed away and watched for a bit as Mom Porcupine returned – probably from doing some foraging.

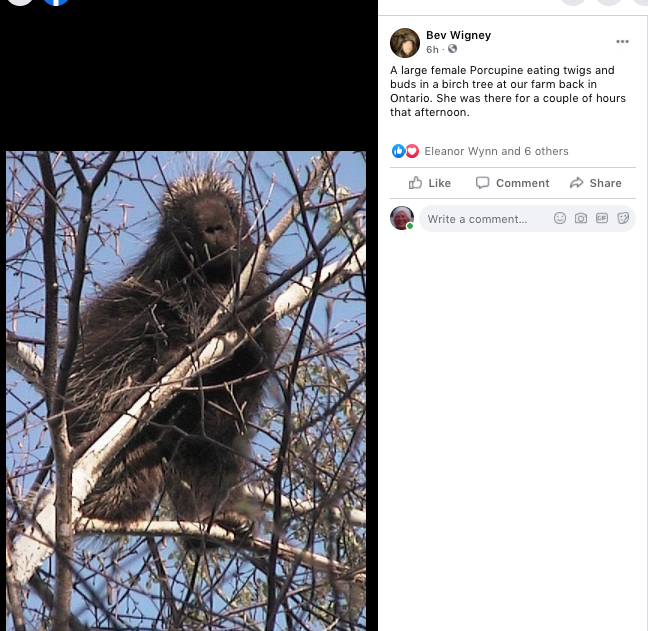

Most of the time, if you find a Porcupine in a tree, it will look more like a furry ball, or even a burl, rather than an animal. Often, the head is not at all visible. However, sometimes the Porcupine will be moving around, as in one of the photos I’ve posted. If you’re lucky, you may get to see it standing up on its hind legs, clawed front and rear feet curled to better grip the branches. They’re really quite beautiful little creatures when you get a chance to see them moving about, albeit rather slowly.

In late winter, you will often find Porcupine tracks in the soft snow. As you can see in the photo I’ve posted, the tracks have quite a distinctive undulating shape. While you may see single sets of tracks on fresh snow, in late winter, it’s not uncommon to find what I refer to as a “porcupine highway” – I’ve posted a photo of that as well. The tracks usually lead from the porcupine’s den to some area where it likes to feed. We found the above tracks on one of the trails at Charleston Lake Provincial Park in mid-March 2006. They led from a den in a crack between two large rocks, to an area where the porcupine had been feeding on fresh branchlet tips on trees towering above the trail. Typical signs of Porcupine feeding activity are dropped branches found below the trees, along with scat and sometimes urine from the animals that have been feeding up above. When we’re out walking along country roads in early spring, we often find branchlets that look as though they they’ve been neatly snipped off at an angle. That’s usually the work of porcupines.

In summer, Porcupine feed on tree buds, leaves, and various plants, but in winter, they are more dependent on tree buds and bark. You’ll often see a tree that has been extensively debarked.

I’ve posted a photo of one — probably the most gnawed tree I’ve encountered. It was a Tamarack (Larix laricina) – this was at Purdon Bog which is in Lanark County, Ontario. The animal has chewed through the outer bark to get at the nutritious cambium (inner bark) of the tree. Tamarack seems to be a favourite of the Porcupine. We’ve sometimes found small trees almost entirely stripped of bark. I’ve posted an additional photo shot from close up so you can see the characteristic gnaw marks of a Porcupine.

Porcupine are fairly docile creatures and don’t generally approach humans. If disturbed, they will usually raise their quills in a way that makes them look larger and a bit alarming. I’ve posted a photo of one doing its quill-raising thing as it waddled off across the trail where I was hiking. Porcupine tend to be solitary creatures – just doing their own thing. They have few enemies, except for the Fisher – which is not as common here as in eastern Ontario. On a couple of occasions, Don and I found an oval patch of quills and hide below a tree — probably the site where a Fisher managed to get the best of a Porcupine.

My family have a bit of a history of spending time out in the woods at their cottages. Just about everyone seems to have a story about Porcupines chewing up something made of wood or leather — things like porch railings, or handles off of tools — anything that would have been held in the hand. The theory is that they are attracted to salt residue on these objects. One other little bit of history to do with Porcupines is a really beautiful Porcupine quill box — made of birch bark and decorated with quill work — that my father bought as a gift for his mother around 1944. He was about 15 and had gone on a several days long bicycle trip with a friend. they pedalled out from Toronto and through the Muskokas. Somewhere along the way, they met an indigenous woman selling her creations at the roadside. My father bought this box and a small birchbark picture frame to bring home to his mother. I still have the box – it’s the one in these photos – with a Moose on the lid!