| SUMMARY

There are many old forest stands in Nova Scotia that developed following blowdown of Old Growth in the Saxby Gale (1869) and the Nova Scotia storm (1871) and thus have maximum possible ages today circa 140 years, the age proposed as the minimum age for three of the forest groups (Tolerant Hardwood, Spruce-Hemlock/hemlock dominant Highland/yellow birch dominant) in the draft Old Growth Forest Policy, up from 125 years in the existing policy.  Pit and Mound topography in Old Growth hemlock/yellow birch forest by Sandy Lake (Bedford, NS). We know these stands succeeded previous stands of very old trees because of the presence of Pit and Mound Topography. Many of today’s stands would be excluded under the proposed Old Growth Forest Policy. The simplest way to solve that issue is to lower the minimum age for classification of a stand in Nova Scotia as Old Growth to 100 years. It makes sense given the sparsity of stands older than 125 years (the current minimum age) now (<0.3%); it makes sense in order to protect more habitat supportive of old forest species (re: previous post); and it makes sense technically, given the history of massive blowdowns in our forests. Related suggestions: – If an existing protected OG stand is subjected to heavy blowdown, extraordinary efforts should be made to retain it as an undisturbed stand rather than be salvage harvested. – The presence of well developed pit and mound topography at a site that is less than the minimum age for OG, e.g., if it comes in at 85 years of age, should be reason to still call the site an OG site in regard to age. – The occurrence of blowdown as an integral natural process in OG forests, whether extensive or more restricted (i.e., blowdown resulting in a gap, rather than stand-replacement) should be taken into account in the sampling protocol, and when a randomly selected sampling position falls in a recent blowdown, another position should be chosen. – Pits and Mounds are special. We should value them – and the processes involved in their creation – for their own sake. |

In my first set of comments on the draft Nova Scotia Old Growth Forest Policy (NSFN Dec 1, 2021), I described how both the 20i2 Old Forest Policy and it’s proposed replacement are weak on conservation of a suite of species associated with old forests, and commented,

I am particularly concerned about the increase in the minimum age from 125 to 140 years for three of the forest groups (Tolerant Hardwood, Spruce-Hemlock/hemlock dominant Highland/yellow birch dominant). From my experience looking at a range of old forests, the 140 years of age requirement would exclude many stands over 100 but less than 140 years of age that possess features supportive of many old forest species, e.g. many large snags; even the 125 year minimum age which applies to six Forest Groups would exclude many such stands.

Hence, as one of the fixes, I suggested to scrap the variable age by Forest Group scheme, and replace it with a minimum age of 100 years.

There is another, somewhat more technical reason I am concerned about increasing the minimum age from 125 to 140 years for three of the forest groups (Tolerant Hardwood, Spruce-Hemlock/hemlock dominant Highland/yellow birch dominant): it would eliminate from potential protection many old stands that developed following a massive storm or storms that crossed Nova Scotia approximately 140+ years ago that blew down many Old Growth stands of the day.

Today, where there are now old stands with some trees >125 years old on these sites, these old forests are growing where there had previously been Old Growth. So the historical continuity of the old forests of today with Old Growth and Old growth processes that goes back 100s of years, or perhaps even millennia.

The reason we know there had been a blowdown of Old Growth in the past – or if not Old Growth by NS’s existing definition, then at least there was blowdown of very big, old trees (likely over 100 years) – is the presence of a pronounced ‘pit and mound’ topography.’

Writing about Old Growth forest in Maine, Joe Rankin, citing Andrew Whitman at the Manomet Center for Conservation Sciences and Shawn Fraver, a professor at the University of Maine’s School of Forest Resources, provided this succinct description:

One other telltale feature of an old growth forest is the forest floor itself, said Whitman and Fraver. It’s not, by any means, level. Instead it’s characterized by dips and mounds. Not coincidentally they’re more or less the size of a large tree’s root ball and its accompanying soil. This “pit and mound” topography occurs when old big trees are blown down, their roots upended. The mound is created by the exposed root ball, the hollow is where it once was. Gradually, over decades, the root rots and both the mound and pit are colonized by mosses, ferns, wildflowers and young trees.

“It could take an old field a thousand years to get that pit and mound topography,” said Whitman. “In managed forests you rarely get that, because large trees are cut before they can fall down”

The lack of pit and mound topography is a good indication that the land was once smoothed by the plow, even if it was a century or two ago*.

__________

*In Nova Scotia, pit and mound topography, even if it exists, can be difficult to distinguish on ground where there are a lot of erratics (big boulders dropped by receding glaciers).

Yellow birch and eastern hemlock on a mound – the “Acadian Forest Love Affair”

The mounds, rather than the pits or dips between the mounds are also the preferred habitat for old growth species such as hemlock and yellow birch, so we see them growing on the tops of mounds, not between them. And upturned stumps resulting from a massive tree falls or much more limited tree fall producing gaps provide cavities for wildlife, mineral soil for seedlings, and often vernal pools; these habitats are transitory, lasting perhaps 5-30 years or so–thus maintenance of such habitats is dependent on more windfalls.

We can estimate the age of a mound – and hence the time of the disturbance that blew the big tree over – from the the ages of the oldest trees growing on those mounds today. For example if a tree on a mound is 140 years old, then that mound must be at least 140 years old. We should add some years to the observed age which is determined on a core taken at breast height to account for the time it took to grow to that height, also the tree might have started to grow only after a few years following the disturbance. So, as a guesstimate, if we add 10 years to the 140-year old tree, we can guess that the event that blew over the big tree to form the mound occurred about 150 years ago. Such a tree today would have started to grow circa 1871.

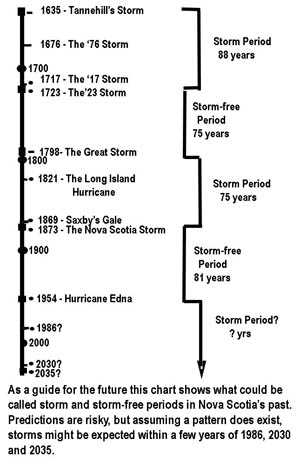

In a very enlightening article titled Woodlands shaped by past Hurricanes, Nova Scotia forester David Dwyer wrote in 1979:

Diagram redrafted from Dwyer, 1979. Click on image for larger version Many of our forest stands in Nova Scotia are a result of past hurricanes. Mounds on the forest floor -the result of uprooted trees – indicate this.The age of trees growing on these mounds give a good indication of when the storm occurred. These stand ages compare well with the written records of past storms… A common age of forest stands in Nova Scotia is 100 years. The origin of many of these stands is the blowdown resulting from Saxby’s Gale.[1869] No doubt the Nova Scotia Storm of 1873 is a contributing factor too. George MacLaren writes in his Pictou Book that the storm of August 24, 1873 “… was probably one of the most severe and destructive that has visited our coast in years”. He calls it “The Big Blow.” |

Dwyer wrote in 1979, so those “100 year old stands” that survive today are circa 142 years old max. Most trees in a multi-aged stand in which the oldest trees are 142 years would be less than 142 years. The Old Forest Scoring Procedure calls for “a minimum of 3 sample plots per stand and measuring the age of one tree at each plot. This should be selected from the most common climax species, and should be larger in diameter than 2/3’s of the basal area…For example, if 9 trees have been tallied, then count back 3 trees from the largest tree tallied.” View Old Forest Scoring – Cruise Procedures for details. It’s a bit complicated but it is clear that if the absolute oldest tree in the stand is 140 years, there is a good likelihood that the “Age of oldest 30% of the basal area” so determined will be less than 140 years and so many such stands would not be categorized as Old Growth.

So it is quite feasible under the existing protocol that a stand that has had no harvesting or other interference for hundreds of years, and that today has at least some trees close to 14o years old but not older because the prior stand was blown down in the Saxby Gale or the Nova Scotia Storm, would not qualify as old growth because of this age requirement – even though it could have all of the other features that characterize Old Growth in spades.

A specific example. The only actual raw data or close to raw data from L&F/NRR’s many assessment of forest stands for OG status that is publicly available is a set of data obtained in connection with their assessment of stands in the Lawlor Lake area of Guysborough County in March 2018:

*Old Forest Assessment in the Lawlor Lake Area of Guysborough County, Nova Scotia by Peter Bush. May 9, 2018. Forest Technical Note No. 2018-01 Nova Scotia Department of Natural Resources.

Executive Summary The Department of Natural Resources (DNR) assessed 27 forest stands in the Lawlor Lake area of Guysborough County in March 2018 in response to public concern about forest harvesting and forest product utilization. DNR used the old forest scoring system, outlined in the Old Forest Policy (2012) to assess these stands. The assessment looked at 12 stands that were recently partially harvested and 15 stands that were planned for partial harvest in the area. DNR found that 2 of the 12 recently partially harvested stands were old growth forest (OGF), and a further 8 were considered old forest that did not meet the criteria for old growth. Of the planned harvest stands (not treated), 11 of the stands were OGF; 1 was old forest; 1 was mature forest, and 2 were immature. Old forest scoring age for all the stands surveyed had a mean of 134 years, with a range of 45- 167 years. The Old Forest Policy currently has 27,825 ha (15.7% of the Eastern Interior Ecodistrict) of conserved OGF and restoration opportunities. An examination of the Pre-treatment Assessment indicator currently used to flag potential stands for old forest scoring found that 5 of the 13 OGF stands in this study would have been flagged if used. The Old Forest Policy and its associated tools (old forest scoring) provides a science-based approach to evaluate OGF and appropriate policy mechanisms to conserve that forest when it is found.

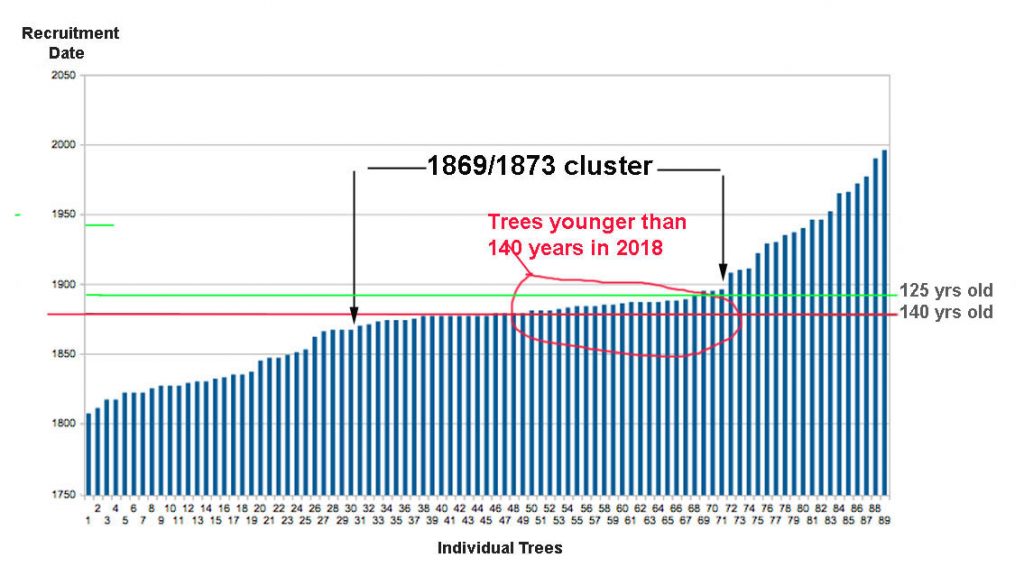

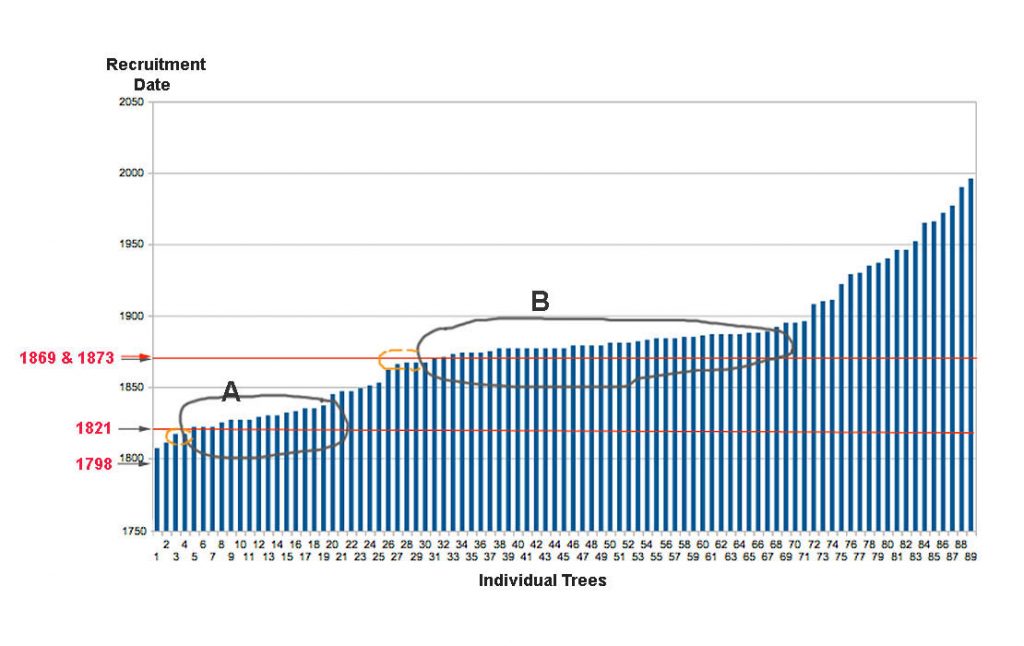

The mean age of 134 years made me wonder of these were stands blown down by some of the storms cited by David Dwyer. In Appendix 4 of the report, the ages of all 89 trees that were aged are given, the related Estimated Recruitment Dates – calculated as 2017 (last ring in tree counts) minus age. So I plotted those numbers sequentially going from the earliest to most recent recruitment date:

Recruitment dates of individual trees in the DNR Lawler Lake study (from Bush 2018) ordered left to right from earliest Recruitment Date to the most recent. Dates in red correspond to storms cited by Dwyer 1979. The envelopes circle plateaus suggestive of a suite of recruitment associated with (A) the 1821 storm, and (B) the 1869 and 1873 storms together. The orange circles to the left are trees that would be included if a few years were added to the recruitment dates to allow the time required to breast height. All of these trees were hardwoods – yellow birch, sugar maple, red maple. (Click on image for larger version)

The plot is pretty suggestive of periods of a lot blowdown and periods of less blowdown as postulated by Dwyer (see diagram above), and of two major blowdown periods (A&B) corresponding to known storms.

Then I looked at how many of the trees in the B cluster – trees that grew following the 1869 and 1873 storms – would be rated as OG (Old Growth) when the age criterion is 125 years (as currently) and when it is 140 years (as proposed in the draft Old Growth Forest Policy for some stands):

Most of the trees in the 1869-1873 cluster are at least 125 years old, but about half are not 140 years or older. So if the critical age were raised from 125 to 140 years, many of these hardwood stands – would not be rated as OG and so not protected. Yet they are all part of the same age cluster.

Is that what we want? I don’t think so.

The simplest way to solve that issue is to lower the minimum age to 100 years. It makes sense in order to protect more habitat supportive of old forest species (re; previous post); and it makes sense technically, given the history of massive blowdowns in our forests.

Is this ‘Science by Social Media’?

I suppose it is, and so might well be discounted by L&F/NRR. However, the announcement of the proposed changes was made only on Nov 9, and we were given until Dec 7 – less than a month – to respond, hardly time to go through regular scientific processes to make the point. There are no interactive sessions where these kinds of issues could be discussed directly in a back and forth discussion with NRR forest scientists and others – that sort of discussion IS part of the scientific process. It’s quite possible I have misinterpreted these data. Fine. Let’s hear about it, let’s discuss it; if not, then it’s all positive input to NRR.

I could, as some of my scientific colleagues are doing, submit a detailed technical comment to NRR, and I will submit these comments to NRR as part of their ‘consultation’ process. I am making the comments public in order to try to open up the discussion of such issues more broadly outside of NRR amongst academics and the broader public – something NRR should also be doing a lot more of (and Prof Lahey said they should be doing a lot more of).

What I would really like to see is for NRR to be much more transparent about their science and to discuss it openly in public forums where they will both inform and be challenged; that will simply strengthen the science, and be good PR; it will engender more trust.

A more specific suggestion in relation to OG: make the full dataset for all of the OG assessments to date fully public, and encourage academics to make use of them, to ‘mine the data’ as it is called. As far as I know, the only such data currently available are those in the Lawlor Lake Report (cited above), and those are only part of the data collected – we don’t know, for example, the amount and volumes and CWD and snags, and canopy closure and abundance different species and so on, all measured as part of the OG assessments. I have been told by one colleague that he requested access to such data, and was refused. (I gave up making such requests some time ago; I did make a request about a week ago, asking if I could be given the percentage of Old Growth in NS by the current definition that NRR estimates occurs in NS, ‘still no reply.)

If the data are ‘put out there’, academics not just in NS but world-wide will begin to make use of them, which can only help our understanding of our forests. Even if there are drawbacks to the definition of OG as given in OFP 2012, Barry et al., 2018 comment that it is one of the few operational definitions of OG, and L&F has applied it in a consistent fashion (we assume) to perhaps 100s of sites. That’s potentially a superb database. An equivalent are the data from the NS Permanent Sampling Plots which have been made widely available have generated some excellent science (e.g., Qi Yang et al., 2017, more) at no cost to us (beyond the maintenance of the Permanent Sampling Plots), and are a credit to DNR/L&F/NRR.

So please please please, NRR, share the OG Forest data in the same way, make them available to anyone on request, or even better – posted in a regularly updated, user-friendly database – even offer workshops on it, that would make for very positive interactions and exchanges.

Some related issues

Mixed forest blowdown on the Chebucto Peninsula. Biggest trees circa 20″ dbh. Likely Hurricane Juan blowdown. It wasn’t salvage harvested, and provides some exceptional, dead-wood rich habitat, with shelter patches.

One is the practice of salvage harvesting. Where there is a lot of blowdown (>25%), the Forest Management Guide for Crown lands currently in use (McGrath 2018) prescribes Salvage Harvesting – “Removal of overstory and merchantable blowdown”. Fortunately, the Silvicultural Guide for the Ecological Matrix (McGrath et al., 2021) has a more moderate approach (p. 59) but there is no express recognition that an Old Growth stand that blows down retains many features of Old Growth, and that blowdown is part and parcel of Old Growth dynamics in NS (as well as much more broadly). Thus in OGFP 2021, Section 5.3, the occurrence of “a large disturbance [that] has killed most of the trees” is cited as a reason to remove protection from an existing protected OG site.

Generally, even with extensive blowdown, there will be a few patches and individual trees remaining intact, which, with the new generation of windthrows will accelerate re-establishment of Old Growth as defined by age. If it is salvage harvested, removing old dead wood, and freshly turned up stumps – both are valuable habitat for a variety of old forest species – and destroying existing Pit and Mound topography in the process, the stand will take centuries to recover the Old Growth features that characterized it before it blew down

Thus I suggest if an existing protected OG stand is subjected to heavy blowdown, extraordinary efforts should be made to retain it as an undisturbed stand rather than be salvage harvested. There may be concern about fire and indeed fires have followed many blowdowns historically but the pit and mound structure is still maintained (Ponomarenko, 2009; and E. Ponomarenko in workshop at Old Forest Conference 2016*). Thus a controlled burn could be preferable to salvage harvest in such instances. And we should at least think about the same options in relation old hemlock-dominated stands that are killed by HWA.

____________________

*E. Ponomarenko, 2009. Reconstruction of Pre-historical and Early Historical Forest Fires in Kejimkujik National Park and Historic Site. Prepared for Kejimkujik National Park and Historic Site Ottawa 2009. MTRI Old Forest Conference, Debert, 2016.

| Update Dec 24, 2021 This report adds to the rationale for prescribed burns of blowdown: Controlled burning of natural environments could help offset our carbon emissions Univ of Cambridge on physical.org. Dec 23, 2021. “A new study has found that prescribed burning can actually lock in or increase carbon in the soils of temperate forests, savannahs and grasslands.” Cites this scientific paper: Adam Pellegrini et al., Fire effects on the persistence of soil organic matter and long-term carbon storage, Nature Geoscience (2021). DOI: 10.1038/s41561-021-00867-1. |

Likewise, I suggest that the presence of well developed pit and mound topography at a site that is less than the minimum age for OG, e.g., if it comes in at 85 years of age, should be reason to still call the site an OG site in regard to age, i.e. if a stand has other features of Old Growth such as an abundance of deadwood, the fact that it has pit and mound topography should override the minimum age requirement.

Finally, the occurrence of blowdown as an integral natural process in OG forests, whether extensive or more restricted (i.e., blowdown resulting in a gap, rather than stand-replacement) should be taken into account in the sampling protocol, and when a randomly selected sampling position falls in a recent blowdown, another position should be chosen. Commonly, only 3 positions are sampled, thus if just one falls in a blowdown, it is likely to result in the stand not being classified as OG.

Valuing Pits and Mounds for their own sake

It is odd that Pit and Mound topography is a commonly cited and extensively researched feature of Old Growth forests in northeastern North America, yet Pit and Mound topography and the associated processes are not cited as features of OG in Old Forest Policy 2012 or in the draft Old Growth Forest Policy 2021 or in associated documents such as the Story Map and the Scoring Protocol. They clearly should be.

Certainly, current L&F/NRR personnel are familiar with them – I credit a DNR hosted field trip and related workshops by Elena Ponomarenko and Donna Crossland at the MTRI Old Forest Conference in 2016 with stimulating my own interest in pit and mounds. Fortuitously, it turned out that early in the following summer I was asked by the Sandy Lake Conservation Association to have a look at flora in the area of Sandy Lake, Bedford for their possible conservation value. I was hesitant to do it… but said I would have a look. As it turned out, st the first place I went to have a there were massive hemlocks and pronounced pit and mound topography. That sold me on the area and I made many repeat visits, in the process learning about and documenting many features of the pit and mound topography. (Prior to that, my main stomping ground was the Chebucto Peninsula, where even in Old Growth stands, any pit and mound topography that might be present is likely to be obscured by the many erratics.)

Dr. Elena Ponomarenko shows participants in the MTRI Old Forest Conference (Oct 19-21, 2016) how to read the forest floor under a mound to reveal records of past disturbances and forest types. In photo Bruce Stewart (NRR), Donna Crossland (Keji ecologist) – and kids!

Learning about Pit and Mounds changed the way I look at these old forests. I began to notice what’s growing on top of the mounds (and not in the pits and dips), to look into cavities created by recent tree falls for plants sprouting there where there is some light, or for signs of animal life in dark cavities, and noting how tree falls can create vernal pools. I noticed that Pit and Mound topography was much less pronounced or entirely absent close to old logging roads and in forest areas that today have very few Big Trees (trees >1/2 m or 20″ diameter at breast height).

But there was something else… Walking through an area with Big Trees and pronounced pit and mound topography, I felt a continuity between the forest of today and the forest of old; it was like ‘talking with the elders’. I led several walks into these areas and introduced others to pits and mounds; repeatedly, people told me it changed the way they look at the forest. One participant was an American woman who was very familiar with old forests in New England but not Pit and Mound Topography – it is much rarer there, even in forests not much older than our many of our NS forests because so much of the landscape was cleared for agriculture in the 17 and 1800s and then abandoned in the latter part of the 1800s and into the 1900s. We have proportionally had much less clearance of land for agriculture in NS, and accordingly more pit and mound topography, although we lose more with each clearcut.

In some places where Pit and Mound topography has been lost, efforts are made to reconstruct them artificially (e.g, view Fox 2017, Graham Buck, 2003.)

So Pits and Mounds are special. We should value them – and the processes involved in their creation – for their own sake.

———————-

SOME RELATED NSFN POSTS, ARTICLES, LITERATURE

As Hurricane Teddy heads our way, some thoughts about our windblown Nova Scotia forests 21Sep2020

Posted on NSFN Sep 21, 2020

If an Old Growth stand in Nova Scotia blows down, is it still Old Growth?

Posted on NSFN Feb 4, 2019

Patterns of pedoturbation by tree uprooting in forest soils

Bobrovsky M.V., Loyko S.V. Russian Journal of Ecosystem Ecology Vol. 1 (1). 2016. A descriptive article with photos. It references classic research by E.V. Ponomarenko who has been working in Nova Scotia recently.

Microtopography and ecology of pit-mound structures in second-growth versus old-growth forests

Audrey Barker Plotkin et al., 2017 Forest Ecology and Management 404 (2017) 14–23 “Pit and mound microtopography is an important structural component of most forests, influencing soil processes and habitat diversity. These features have diminished greatly in northeastern U.S. forests since European set- tlement, as a result of the history of repeated logging, land-clearance followed by reforestation, and the smaller size of trees (and therefore windthrow features) comprising the prevailing second-growth forests…Pit-mound structures are a diminished component of second-growth forest, and silvi- cultural techniques designed to restore old-growth characteristics could include measures to preserve and en- hance pit-mound features, and to cultivate large-diameter trees that will eventually create the large, long-lasting pit-mounds of the future.”

The variety of soil microsites created by tree falls

Susan W. Beatty and Earl L. Stone, Canadian Journal of Forest Research • June 1986

Woodlands shaped by past Hurricanes

By David Dwyer, NSDNR Forester (originally published in Forest Times November 1979).

Uneven Ground

Bt Akiva Silver, Chelsea Green Publishing, 2019. “An excerpt from my book Trees of Power published by Chelsea Green” It begins: “Here in upstate NY there are hills everywhere but the ground upon them is flat. The fields of our hillsides are easily mowed and grazed. They were smoothed out a long time ago when they were first cleared and plowed. It did not always look like neat rolling hills here. Ancient hardwood forests created a ground so uneven, textured, and three dimensional, that it resembled mogul ski runs. These types of forest floors still exist today on the steepest hillsides that have been woods for centuries. Walking in an old forest around here is more like climbing up and down pits and mounds of soil than strolling down a trail. The topography is so intricate that one hillside is actually made up of thousands of micro hills and valleys.”

Acadian Forest Love Affair

by David P (Jan 26, 2018) on sandylakebedford.ca. The physical intimacy of yellow birch and hemlock often observed on mounds in old forests is more than a coincidence.

Woodlands shaped by past Hurricanes

By David Dwyer, NSDNR Forester (originally published in Forest Times November 1979).

Pondering the PIT & MOUND TOPOGRAPHY at Oakfield Park, Nova Scotia

YouTube video by Bob Guscott (retired DNR forester) and David Patriquin (NSFN), Nov 8, 2017

Was this Woodlot once Farmland? Pit and Mound Formation will tell you

YouTube video by Mike & Debbie Hickey in their From the Woodlot video series, N.B. Posted May 5, 2020. Nice description of a recent windfall, and showing an area of pits and mounds in their woodlot which they contrast with flat topography over most of the area.

Pit and Mound topography on a private woodlot in Central NS. Hemlock & Yellow birch together on a mound at right (the “Acadian Forest love Affair”). The oldest trees in this forest are circa 140 years old. See Thanks for sensitive management of an old forest in Nova Scotia

Post on NSFN Oct 8, 2018