SUMMARY

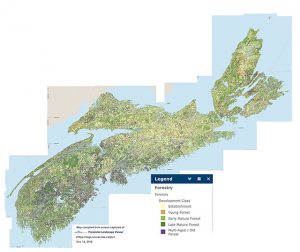

Distribution of forest in 5 development stages across Nova Scotia, compiled from NS Landscape Map Viewer in 2018. Purple = Multi-aged/Old Forest. Dark Green=Late Mature Forest. Click on image for larger version. View larger versions of the map: 2000 px | 4000 px.

The dark green and purple patches correspond, more or less, to ‘Old Forest’ – forest 80+ years old. Today it is most concentrated in SW Nova Scotia where there is a high proportion of Crown land and where a consortium of mills (“WestFor”) is harvesting these older forests.

Big Forestry in Nova Scotia, the forestry folks in the Nova Scotia government and the federal forestry folks in Canada like to point out that there has been very little deforestation in Nova Scotia and in Canada at large, and consequently that “Canadian forests are healthy, productive and thriving.”

Critics have maintained that while the forest cover may not have changed much, forest degradation has occurred though conversion of older forest to younger forest and though species simplification, resulting in reduced carbon storage, and losses in biodiversity.

Forest degradation, defined as ‘the human-induced loss of carbon stocks within forest land that remains forest land’ is addressed in international agreements to which Canada is a signatory and in principle is accounted for by changes in carbon stocks (essentially wood volumes). The forest industry and many governments including the feds contend that such losses are not the same as deforestation because ‘the forest grows back’, and so deflect attention to deforestation, especially in tropics where there is a lot of deforestation. Further, the existing system of carbon accounting obscures the specific gains and losses associated with logging by ‘throwing it all in one basket’.

Industry and government have been able to largely ignore the effects of forest degradation defined more broadly as loss of ecosystem services because except for carbon storage, ecosystem services are not so readily measured.

That changed with the The ‘2022 bird study’; it illustrates conclusively that forest degradation in the Maritme Canada region in the form of loss of Old Forest, not just loss of Old Growth forest, has led to large declines in bird populations across many species. (For NS, Old forest is forest 80 and more years of age & Old growth, 125 and more years of age.)

In Nova Scotia, such losses continue today primarily via ‘high grading at the landscape level’: the harvest of remaining patches or stands of old trees/older development stages in landscapes where there has been extensive clearcutting over the last 30-40 years.

Current Landscape Level goals for Old Forest conservation in NS are limited to protection of Old Growth and some 0lder forest, the latter mostly in existing protected areas. Protection of Old Growth (forests 125 years and older) is not controversial because there is such a small amount (0.3% or less by area), that its protection has essentially no impact on wood supply from Crown lands.

The Old Forest Policy protects approximately 10 % of Crown lands, most of it as potential Old Growth, and most of it is in existing protected lands so it is not sought by sawmills; about half of the land so protected is Old Forest currently; but because Crown lands are only about 1/3 of forested land, the Old Forest Policy protects less than 3% of the forest land in NS as Old Forest compared to perhaps 15% in total.

We urgently require a Precautionary Landscape Level Plan for Old Forest conservation. An example of how that might look is suggested based on the recommendation of Mosseler et al. 2003 that at least 20–25% of our forest be maintained in late-successional forest types.

The Triad system that NS is currently putting in place for management of Crown lands is intended to minimize the tradeoffs involved in managing forests to serve the need for both extraction of wood, and to maintain the forests’ multiple, non-extractive values (“Ecological Services”).

The Triad is “inherently landscape-oriented and intentionally planned” (Hines et al, 2022); that landscape level planning is the piece is still lacking in Nova Scotia.

It’s important to recognize that the Triad is not a proven system but a concept and now a few experiments in which there is widespread interest. Its application in NS is the biggest trial of it yet. Many people and institutions outside of NS will be watching how it unfolds and very likely conducting rigorous independent assessments of how well it works socially and in regard to achieving the desired balance between wood production and ecological services.

The current government has committed to full implementation of the Triad by 2023. Just how it unfolds and in particular how current Old Forest is assigned to each of the 3 components of the Triad and how much wood is harvested in successive years will determine whether Old Forest cover in NS continues to decline, remains at current levels, or, as we need in order to reverse losses in biodiversity, increases.

View details under Consultations/News & Comment/On Reversing Forest Degradation in Nova Scotia