A remarkable story was published this past week:

Finding The Mother Tree: Discovering The Wisdom Of The Forest by Suzanne Simard, 368 pages, Published:May 4, 2021, by Penguin Random House. Listed at $Can $34.95

It’s remarkable in many respects: as a scientific story that is effecting a “paradigm change” in how we think about forest ecosystems; as a very personal story that intersects with the author’s own health challenges; as a story that revealed/confirmed indigenous perspectives on forest communities; and very much more. For a quick review, read Finding the Mother Tree by Suzanne Simard review – a journey of passion and introspection

Tiffany Francis-Baker in The Guardian, May 8, 2021. Also view A pioneering forest researcher’s memoir describes ‘Finding the Mother Tree’, a CBC April 30, 2021 article and interview.

I had ordered a hard copy, but also got a Kindle copy which I skimmed in 3 or 4 hours; ‘can’t wait to receive the hard copy in a couple of weeks, and to take the time I need to really absorb and enjoy it. The writing is anything but dry. It’s a very personal story, often raw, but at once honest, enticing and very informative. It’s about Simmard as a woman challenging a men’s world and as a scientist challenging some entrenched scientific concepts and as a forester challenging entrenched perspectives on sustainable forestry. There is lots of natural history in it that you won’t get elsewhere, about the BC forests, about the soils and the mycorrhizae and the trees and fungi and pests and salmon. It’s very fundamentally about life on planet Earth. It is wonderfully illustrated with black and white photos from days gone by and colour photos of forests, trees, roots, mycorrhizae and wildlife.

Suzanne Simard joined the faculty at the University of British Columbia in 2002. She was 41 years of age, and came with a good helping of life experience including lots of forestry credentials besides her degrees: she was the first female worker for a logging company, worked as an applied forestry researcher (mostly related to plantations) for the BC Government and came from a strong family background in forestry.

I came from a family of loggers. My great-grandfather and my grandfather and my great-uncles and my dad and his brothers all horse logged. And so, I grew up around this. You know, my grandfather and my great-uncle, they built all their own flumes and their own water wheels to generate electricity, their own logger’s houseboats. They – you know, their words, their boats – everything was handmade, and everything was slow and small. And so – of course, to me, it was just the way of life. (NPR Author Interview).

Her “Uncle Joe” Gardner was Dean of forestry at UBC between 1965 and 1983; Simmard modestly did not mention in a webinar that Uncle Joe (also known affectionately as “Uncle Joe” to all the students) “brought women into the undergrad forestry programs at UBC – the previous dean did not allow women to register in forestry, when Dean Gardener found out about that he quickly changed it and there was an explosion in the number of women students (Sally Aiken in Dispatches from The Mother Tree Project).

To Simmard, the move to a university meant she “wouldn’t have to stick with the mandate of the Forest Service; I could do anything I wanted with whatever grant money I gathered. I could get at the basic questions of relationships in the forest, which had deepened from ideas about connection and communication between trees to a more holistic understanding of forest intelligence.”

More or less where the research had led up to at that point is illustrated in this publication (Simmard was a co-author):

| – Ectomycorrhizae and forestry in British Columbia: A summary of current research and conservation strategies Alan M. Wiensczyk et al., 2002 in B.C. Journal of Ecosystems and Management. Focus is on ectomycorrhiza. These benefits of ectomycorrhizal fungi for tree growth are cited (references excluded):

These management practices are advised to maintain “these beneficial plant/

|

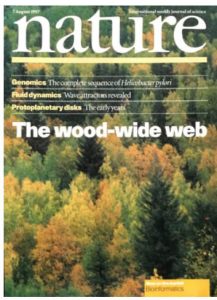

Cover of the August 1997 issue of Nature, where the term “wood-wide web” was coined in reference to the paper “Net transfer of carbon between ectomycorrhizal tree species in the field” by Simard et al.

Prof Simard’s reputation had received a major launch, both negatively and positively, when some of her PhD research providing the first evidence for “bidirectional transfer” of nutrients between different species of trees via mycorrhizal (fungal) networks, was published in the prestigious scientific journal Nature in 1997; not only as a paper in Nature but as the cover article as well.

Net transfer of carbon between ectomycorrhizal tree species in the field. S.W. Simmard et al., 1997: 579-582

…If our results reflect the magnitude of carbon transfer in natural systems, then the net competitive effect of one species on another cannot be predicted without a better understanding of interplant carbon transfer through shared mycorrhizal fungi and soil pathways. A more even distribution of carbon among plants as a result of belowground transfer may have implications for local interspecific interactions, maintenance of biodiversity, and therefore for ecosystem productivity, stability and sustainability

Her findings, or at the least the concepts she used in describing them, were dismissed by some or even many – and, as described in Finding the Mother Tree, are still meeting a lot of resistance.

At UBC, Simard focussed on the extent, nature and properties of mycorrhizal associations with forest trees, particularly the ectomycorrhizae. (View Natural History/Mycorrhizae on this website for more about mycorrhizae generally). The concept of “Hub Trees”, which she later described as “Mother Trees”, emerged circa 2008 and was elaborated in detail by graduate student Kevin Beiler (bolding inserted):

[Beiler] has uncovered the extent and architecture of this network through the use of new molecular tools that can distinguish the DNA of one fungal individual from another, or of one tree’s roots from another. He has found that all trees in dry interior Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii var. glauca) forests are interconnected, with the largest, oldest trees serving as hubs, much like the hub of a spoked wheel, where younger trees establish within the mycorrhizal network of the old trees. – Suzanne Simard in Do Trees Communicate (YouTube Video, 2011)

For more details, view Architecture of the wood‐wide web: Rhizopogon spp. genets link multiple Douglas‐fir cohorts

Kevin J. Beiler et al., 2010 in New Phytologist 185: 543–553. Also: The foundational role of mycorrhizal networks in self-organization of interior Douglas-fir forests by S. Simmard, 2009, Forest Ecology and Management 258S (2009) S95–S107

There was lots more going on as she wrote about in 2010:

Through careful experimentation, recent graduate Francois Teste determined that survival of these establishing trees was greatly enhanced when they were linked into the network of the old trees.Through the use of stable isotope tracers, he and Amanda Schoonmaker, a recent undergraduate student in Forestry, found that increased survival was associated with belowground transfer of carbon, nitrogen and water from the old trees. This research provides strong evidence that maintaining forest resilience is dependent on conserving mycorrhizal links, and that removal of hub trees could unravel the network and compromise regenerative capacity of the forests.

In wetter, mixed-species interior Douglas-fir forests, graduate student Brendan Twieg also used molecular tools to discover that Douglas-fir and paper birch (Betula papyrifera) trees can be linked together by species-rich mycorrhizal networks. We found that the mycorrhizal network serves as a belowground pathway for transfer of carbon from the nutrient-rich deciduous trees to nearby regenerating Douglas-fir seedlings. Moreover, we found that carbon transfer was enhanced when Douglas-fir seedlings were shaded in mid-summer, providing a subsidy that may be important in Douglas-fir survival and growth, thus helping maintain a mixed forest community during early succession. This is not a one-way subsidy, however; graduate Leanne Philip discovered that Douglas-fir supported their birch neighbours in the spring and fall by sending back some of this carbon when the birch was leafless. This back-and-forth flux of resources according to need may be one process that maintains forest diversity and stability.

A couple of concepts Simmard has advanced appear still to be difficult for many to accept as “scientific”, as described in detail in Finding the Mother Tree. One is that trees in effect “talk to each other” via mycorrhizal networks and that there is something approaching intelligence (or perhaps even consciousness, although she doesn’t use that word) in the way they are able to respond to environmental cues, and recognize and give special support to their own kin; this concept she also discovered is very much part of how the indigenous cultures view the forests. Said Simmard in an interview with Yale e360 in 2016:

e360: You’ve talked about the fact that when you first published your work on tree interaction back in 1997 you weren’t supposed to use the word “communication” when it came to plants. Now you unabashedly use phrases like forest wisdom and mother trees. Have you gotten flack for that?

Simard: There’s probably a lot more flack out there than I even hear about. I first started doing forest research in my early 20s and now I’m in my mid-50s, so it has been 35 years. I have always been very aware of following the scientific method and of being very careful not to go beyond what the data says. But there comes a point when you realize that that sort of traditional scientific method only goes so far and there’s so much more going on in forests than we’re able to actually understand using the traditional scientific techniques.

So I opened my mind up and said we need to bring in human aspects to this so that we understand deeper, more viscerally, what’s going on in these living creatures, species that are not just these inanimate objects. We also started to understand that it’s not just resources moving between plants. It’s way more than that. A forest is a cooperative system, and if it were all about competition, then it would be a much simpler place. Why would a forest be so diverse? Why would it be so dynamic?

To me, using the language of communication made more sense because we were looking at not just resource transfers, but things like defense signaling and kin recognition signaling. The behavior of plants, the senders and the receivers, those behaviors are modified according to this communication or this movement of stuff between them.

Also, we as human beings can relate to this better. If we can relate to it, then we’re going to care about it more. If we care about it more, then we’re going to do a better job of stewarding our landscapes.

In a paper published in 2009 on “Mycorrhizal networks and complex systems: Contributions of soil ecology science to managing climate change effects in forested ecosystems“, Simmard discusses “how soil ecologists can adopt a complex systems approach to research and management to help address changing species distributions, disturbance regimes, and ecosystem resilience with climate change…A more integrated understanding of the role soil organisms play in organizing and stabilizing ecosystems, for example, will help us manage native and exotic plant species diebacks and migrations… or mitigate changes in nutrient availability, carbon sequestration and soil stability.” UPDATE May 11, 2021: ‘Informative discussion with Simmard on this topic in Scientific American: ‘Mother Trees’ Are Intelligent: They Learn and Remember (May 4, 2021).

An area of windfall on a hill by St. Margaret’s Bay, N.S. that was not salvage harvested harvested is a wildlife refuge

A second concept has to do with the value of dying Mother Trees and how they attempt to pass on as much benefit as they can to their kin as they are dying. Simmard became especially immersed in this concept when she herself got breast cancer which spread to her lymph nodes and as a mother wanted to understand how she could deal with her own passing in relation to her children. It’s a very moving personal story which she describes in Finding the Mother Tree, but also has practical implications, especially in regard to salvage harvesting – which we do a lot of (and I think far too much) in windy Nova Scotia!

In 2015, Simard established the Mother Tree Project to investigate how we can design forest renewal practices -i.e., harvesting and planting – so that we can keep these mycorrhizal systems as nearly intact as possible in order to maintain biodiversity, carbon storage and foster regeneration as climate changes. “Today, people are still trying retention forestry, but it’s just not enough. Too often it’s just the token trees that are left behind. We’re starting on a new research project to test different kinds of retention that protect mother trees and networks. –Simard in 2016

It is a massive, complex experiment/set of observations involving “three basic factors …one is a climate gradient –second is retaining these old trees, we call them mother trees because of their nurturing capabilities… and thirdly we wanted to look at a seedling genetic gradient – so as climate changes, how do we assist migration of certain genotypes so that they’re better adapted to the future climates..”

A fascinating, quite comprehensive and easy-to-follow overview of the design and the results to date is provided in a webinar video:

Suzanne Simard – Dispatches from The Mother Tree Project (YouTube)

UBC Forestry Oct 22, 2020. From the description:

Any forester will tell you that different trees have different value, and that value is generally set by the marketplace. But what if the value of some trees is below ground rather than above it?

This is the central question of The Mother Tree Project, which is providing scientific data to help direct management of forests under a changing climate. …

Mother trees are typically the biggest trees in the forest, and they connect to other trees via a vast underground mycorrhizal network. It is well known that these networks allow trees to share resources and even alert each other to threats. Mother trees also support forest regeneration by providing resources to seedlings.

Suzanne’s research has shown that trees become more dependent on mycorrhizal networks when they are stressed, such as in hotter and drier climates. So the Mother Tree Project is experimenting with a range of forestry practices in different climatic regions, to learn how to create more resilient forests for the future.

The results are reported in ongoing publications with some pretty specific management recommendations e.g.,

Partial Retention of Legacy Trees Protect Mycorrhizal Inoculum Potential, Biodiversity, and Soil Resources While Promoting Natural Regeneration of Interior Douglas-Fir, Suzanne W Simard et al., 2021. From the Abstract:

Clearcutting reduces proximity to seed sources and mycorrhizal inoculum potential for regenerating seedlings. Partial retention of legacy trees and protection of refuge plants, as well as preservation of the forest floor, can maintain mycorrhizal networks that colonize germinants and improve nutrient supply. However, little is known of overstory retention levels that best protect mycorrhizal inoculum while also providing sufficient light and soil resources for seedling establishment. To quantify the effect of tree retention on seedling regeneration, refuge plant diversity, and resource availability, we compared five harvesting intensities with increasing retention of overstory trees (clearcutting (0% retention), seed tree (10% retention), 30% patch retention, 60% patch retention, and 100% retention in uncut controls) in an interior Douglas-fir-dominated forest in British Columbia… This study suggests that dispersed retention of overstory trees where seed trees are spaced ~10–20 m apart, and aggregated retention where openings are <60 m (2 tree-lengths) in width, will result in an optimal balance of seed source proximity, inoculum potential, and resource availability where seedling regeneration, plant biodiversity, and carbon stocks are protected.

While the research was conducted in B.C. and mostly on coniferous species, other studies have confirmed the presence of similar networks in virtually all forests. The research results are especially relevant to Nova Scotia, where a lot of the growing conditions could be described as highly stressful, related to strong winds, shallow soils and poor nutrient supply over much of our forested lands.

Mixed Acadian forest on nutrient poor, highly acidic windblown lands by Lower Trout Lake on the Chebucto Peninsula

Despite those stresses, left mostly undisturbed, magnificent forests can develop in NS, as we can see in some of our protected areas and in the broader landscape where there has not been clearcutting.

The challenge, as we all know, is to practice forestry in a way that allows those magnificent forests to be sustained in an era of increasing stresses. Our Department of Lands and Forestry and Big Forestry (the Big Players) maintain that their practices in Nova Scotia are “sustainable” but really, with next to no evidence as intensive clearcutting began only in the 1960s and 1970s’; as well, there are many areas that are not regenerating properly which is what would be predicted based on the Simard group’s and other research.

My reading of various of the papers by the Simard group suggests that Irregular Shelterwood silviculture as described by Prof Bob Seymour and recommended by the Lahey Review as the major practice in the Ecological Matrix would, perhaps with a little fine tuning, meet the kinds of management required to maintain healthy mycorrhizal networks on Crown lands, but shelterwood/2-stage clearcuts and variable retention of 10-30%, which are currently predominant on Crown lands, would not. The Simmard group’s research gives reason to be concerned also about effects of excessive salvage harvesting, reliance on plantations and planting trees, mechanical damage to soils, use of herbicides on the integrity of mycorrhizal systems and hence on their many benefits, especially in relation to mitigating and adapting to climate change.

So will this ground-breaking research receive any attention from the Powers that Be in forestry in NS?

One would think it is highly relevant to understanding our Natural Disturbance regimes, and efforts to simulate them in our forestry practices. However the recent review of natural disturbance regimes in Nova Scotia by AR Taylor et al., 2020 makes no mention of fungi except as pathogens. Perhaps* it will come up in their 2nd paper, on the application of natural disturbance regimes to forestry practices:

Although application of natural disturbance regime information to forest management planning (e.g., how to derive harvest rotations and target age structures by ecoregion, and what residual stand structures reflect natural disturbance regimes) is beyond the scope of this review, a follow-up paper on methods of application is currently being prepared that focuses on translating disturbance parameters …into practical forest management guidelines. – AR Taylor et al., 2020

____________

*Unfortunately, efforts to have some input to this process by some of the critics, including myself, who had highlighted difficulties with L&F’s prior interpretation of Natural Disturbance regimes were firmly rebuffed.

In The Narwhal, May 5, 2021

The constant defence of existing forestry practices by government and industry foresters in Nova Scotia and strong resistance to significant change – even after 11 years of promising such change is hardly unique to N.S.; even in B.C. where Simmard’s research is based and has government support and is pretty well known, there has been essentially no change on the ground.

Interviewer: Quite a lot of people are asking…what are the kinds of responses to your research from forestry companies or governments…do you feel your research has contributed to changing the practices at all?

Simmard: Well I would say if you look at what is happening on the landscape, that we are still not leaving old trees that are valuable, big old trees, we are still taking them, we are still clearcutting for the most part; if I look at it across the board I would say that It hasn’t been very well adopted, these ideas. But that is why I have got the Mother Tree Project, ‘is trying to provide an example and places where people can come and see what this looks like, that there are solutions, alternatives to clearcutting so I am hoping that with public pressure on governments not to clearcut more old growth or to take more old growth, and to reduce the clearcutting…that there will be pressure to move things in a different direction so this new science is better adopted. – From Can Geo Talks with Suzanne Simard May 6, 2021

Indeed, Simmard’s “new science” involves a “paradigm-shift” and such shifts are typically met with strong resistance at first.

| UPDATE May 22, 2021: Simmard is more outspoken in this interview: In the forest, a B.C. scientist discovers trees take care of their own, By Bill Metcalfe North Island Gazette May 20, 2021. As summarized in TreeFrog for May 21, 2021: Suzanne Simard [does] groundbreaking scientific research into mycorrhizal fungi and networks, finding that forests behave as a single organism. …“The industry really shouldn’t be clearcutting if we’re trying to save carbon and save biodiversity and foster regeneration,” she told the Nelson Star, “We should be doing partial cutting.” …Simard says … the tendency of foresters to use herbicides to eliminate deciduous trees in favour of more commercially valuable conifers is a direct threat to healthy forest biodiversity, and is an example of how far behind the times forest policy is. “The plan is to take every last stick, basically. The government needs to shape up. And the problem that they have is that they’ve sold us out. The big corporate industry giants have consolidated, they’ve got their hands on most of the tenure, we’ve made commitments to them for volume harvested, and the government doesn’t want to reduce the timber volume.” |

In the interim, I think Simmard’s concepts will be more readily grasped and appreciated by naturalists and the lay public than by foresters, whether in British Columbia or Nova Scotia; they are already integral to ways indigenous peoples including the Mi’kmaq view and manage forests (e.g., listen to Sa’qawey Nipukt: Old Forests as Mi’kmaw ecologist, Shalon Joudry tours Mi’kma’ki for stories about Old Forests)

On my part, I have for a while been obsessed with “Big Trees” which for Nova Scotia I describe as any tree of at last 20″ or 1/2 meter dbh (diameter at breast height); I generally record the species, location and diameter of all that I encounter and report many of them on iNaturalist (e.g., view Big Trees of Sandy lake & Environs). Now, having read Simmard’s Book and many of the related papers, I am even more obsessed with these trees – and even more concerned about the rush to cut so many of them down as prices for lumber soar to new highs.

So I hope that many in Nova Scotia will read Finding the Mother Tree and that it can help us find better ways, much better ways, of interacting with our own, very special Acadian, Miꞌkmaꞌki forest, and even with each other.

View of Lower Trout Lake (Chebucto Peninsula) from “the climbing tree” (32″dbh) on Aug 12, 2009. The trees towering above the rest are red spruce. (Click on image for larger version.)

——-

Suzanne Simard | Mother Trees and the Social Forest (YouTube Video)

Long Now Foundation Jun 15, 2021

———–

The destruction of the last old growth forests has to stop. We must protect the mother trees

Suzanne Simard

Contributed to The Globe and Mail Published June 11, 2021

https://www.theglobeandmail.com/opinion/arcle-the-destrucon-of-the-last-old-growth-forests-has-to-stop-we-must/

text:

Photo: A woman, who was among activists trying to stop the logging of old growth timber, embraces the stump of a large tree in a cut block of Tree Farm licence 46 near Port Renfrew, British Columbia, Canada on May 17, 2021.

JENNIFER OSBORNE/Reuters Suzanne Simard is a professor of forest ecology in the faculty of forestry at the University of British Columbia and the author of Finding the Mother Tree: Discovering the Wisdom of the Forest. This piece was written in consultation with her colleagues Teresa (Sm’hayetsk) Ryan, Rachel Holt and Tara Martin.

Around the world, mothers are cherished and celebrated for the cycles of birth and nurturing of young lives. Mothers hope above all other things for a happy, healthy life for their children, for future generations.

But mothers today, and their children, fear for the future. Our economic system preferentially degrades nature in favour of expedient dividends for a few, putting us all at risk.

As an ecologist in British Columbia I discovered that trees are connected through below-ground fungal networks and that they communicate with each other and form complex societies similar to our families. After decades of research and hundreds of journal articles published, I have cometo understand forests as intelligent systems built on sophisticated relationships with all creatures, including people.

The biggest, oldest trees are mother trees that recognize and nourish their own kin. The interconnected nature of forests has been known for thousands of years by the Indigenous peopleof North America and the world over that all life is woven together as one.

One time when my daughters were young I brought them to a logging site and we watched the felling of a giant tree.

The thunderous “whomp” of the tree landing on the Earth drowned out the gnawing echoes of the chainsaws that had just severed through her heartwood.

My children and I stood in stunned silence. Her thousand-year old weight crushed her saplings; the needles and cones dropped to the ground. Her roots and their fungal networks that had tied the family together and provided their nourishment frayed and snapped with the weight of heavy machinery.

My oldest daughter stared in shock; my littlest one cried.

We were standing witness to the falling of some of the last of the mother trees, the very life support systems of my children’s future.

It is for this reason that I join my female colleagues, and mothers around the world, in decrying the destruction of the last of the old growth forests.

It must stop.

Forests are being felled at breakneck speed, pumped by a disease of greed and folly, and this is occurring worldwide, not just here in British Columbia.

Many of the tropical rainforests of Borneo, Ghana and the Amazon, the taiga of Russia, and the temperate rainforests of the Oregon Cascades, have already been felled.Even the boreal forest ofCanada that grows at glacial speed owing to the high latitude conditions are being clearcut to supply wood pellets to burn in Europe under the guise of biofuels.

Globally, forests represent one-third of earthly ecosystems, store more than four-fifths of terrestrial carbon, and take up one-third of man-made greenhouse gases. The photosynthetic energy they produce drives our biogeochemical cycles: purifying our air, modulating precipitation, and storing organic carbon and nutrients.

These systems exist in a fragile balance that supports life on this one planet, Mother Earth.

Citizens are begging our elected leaders to stop the exploitation, but the ears of politicians are filled with false assurances from corporate heads. They whisper hollow promises of employment even as mills close, jobs are lost to mechanization, and forest companies move elsewhere once the last sticks are cut and the creeks are full of silt.

On southern Vancouver Island at Fairy Creek, people are protesting against complicit government authority, which continues to target the last 3 per cent of the island’s old growth.First Nations who struggle to eke out an economy, deprived from them by colonialism, are given the “Hobson’s choice” of harvesting the last of their own watersheds or watching someone else cut it.

Corporate lobbyists espouse that replacing old-growth forests with new plantations, trillions of new seedlings, will sequester and store more carbon.

This is simply not true.

Half of the carbon stored is lost to the atmosphere almost immediately with clearcutting of old forests, and it takes decades to achieve carbon neutrality, and decades more to recover the sink strength of the original conifer stands.

Climate models show we don’t have decades for these forests to recover.

In the hundred years it takes for a forest to mature, our planet will have warmed by upward of 5 C, eliciting mass starvations, migrations and war.

More COVID-like viruses might escape from the spaces of destroyed wild places and infect our populations again and again. The risk of catastrophic fire is amplified as old-growth forests are replaced by monocultures of plantation timber. This is not the future we want to leave our children.

What can be done about this?

First, scientists have evaluated the negative effects from forest losses and these results must be used to inform forest management and protection to reduce the risks. The COVID-19 vaccine is atestament to how rigorous scientific determination and political support can rapidly drive solutions to complex problems.

Just think of what we could do if we focused our attention on solving the climate and biodiversity crises, rather than insisting they don’t exist or treating them as too hard to solve?

Second, strive for a close, protective relationship with nature. Support putting a price on carbon, water degradation and biodiversity loss as an essential step for protecting forests as part of the economic system.

Regulate and monitor the activity of logging companies as conditions of the license to harvest while protecting the integrity of ecosystems and their functions. Those responsible for damages should bear the costs.

Third, take immediate action to protect and restore old-growth ecosystems for their value in storing the greatest amounts of carbon, providing habitat for endangered species and maintaining life-sustaining ecosystem functions and services.

Our relationship with nature is fragile. We are obligated to restore our responsibilities to care for Mother Earth for future generations.Let us take these steps to ensure that mothers and mother trees can continue to nourish us all.

Nick Hill at the Climbing Tree – just before he climbed the tree and took the photo overlooking Lower Trout Lake. These Big Trees could be seen on Google Earth. Red Spruce is a signature tree of the Acadian Forest and is the provincial tree of Nova Scotia. (Photo by David P)