For the sake of the forests and salmon, it’s time for NSDNR/Westfor to heed the science and put the brakes on clearcutting in SW Nova Scotia.

I was pleased to read in the Dec 2016 issue of Rural Delivery that NSDNR soil scientist Kevin Keys is participating in a 3-year experiment to examine the efficacy of liming forests for the benefit of salmon and trout in Nova Scotia river systems stressed by acid rain.

The experiment is being conducted along the West River/Sheet harbour where in 2005 the NS Salmon Association set up a lime doser which feeds powdered lime mixed with water directly into the river. The lime increased calcium levels and pH which resulted in many more salmon smolts going out from the river. Smolt numbers increased from about 2000 initially to 10,000-12,000 recently.

Now the Nova Scotia Salmon Association and the Eastern Shore Wildlife Association, with the support of Fisheries and Aquaculture and NSDNR and federal agencies have started some liming on adjacent forested land using helicopters. Based on experience in Europe, it is hoped that terrestrial liming will be cheaper than adding lime directly to the water, involve much lower maintenance and be more effective over a larger portion of the watershed as well as for long periods of time. (If the lime doser stops, the water acidifies very quickly).

The terrestrial liming at West River/Sheet harbour follows and is informed by two smaller-scale terrestrial liming experiments conducted on smaller catchments located within the Gold River Watershed in New Ross, Nova Scotia under the direction of Dalhousie researcher Shannon Sterling. It’s pretty complicated stuff, with a lot of site to site variation, and precautions have to be taken not to negatively impact acid-loving species.

If successful, the approach could be used on other watersheds in the southern uplands of Nova Scotia. Rivers in SW Nova Scotia have been the most strongly affected by acid rain. Further, unlike other regions in northeastern North America which have seen a response to controls on smokestack emissions, pH and calcium have continued to decline in many watersheds of SW Nova Scotia, an anomaly attributable to the exceptionally poor buffering (nutrient supplying) capacity of the affected landscapes.

If successful, the approach could be used on other watersheds in the southern uplands of Nova Scotia. Rivers in SW Nova Scotia have been the most strongly affected by acid rain. Further, unlike other regions in northeastern North America which have seen a response to controls on smokestack emissions, pH and calcium have continued to decline in many watersheds of SW Nova Scotia, an anomaly attributable to the exceptionally poor buffering (nutrient supplying) capacity of the affected landscapes.

While the prime target of the liming is salmon, it is expected that brook (speckled) trout and likely other aquatic species from zooplankton to loons could benefit – and the forests themselves. Many studies have shown that declines in calcium under forests have diverse adverse effects either through calcium deficiency directly or indirectly through increased acidity, aluminum mobilization and enhanced mercury toxicity e.g., on cold tolerance of red spruce, sugar maple decline, forest salamanders and snails, forest herbs, invertebrates and song birds. So it makes sense that NSDNR is taking an interest in the liming experiments.

In the Rural Delivery article “Salmon and Soils”, writer Zack Metcalfe describes Kevin Keys/NSDNR involvement:

While the project is aimed at restoring West River Sheet Harbour, terrestrial liming also has the potential to benefit forests. Kevin Keys, a site productivity forester with Nova Scotia’s Department of Natural Resources, is an aficionado of dirt. He and others will be studying the impacts of terrestrial liming on the soil itself, taking samples from limed and unlimed areas and gauging the potential for speeding up forest recovery in regions diminished by acid rain.

“Forest soils in Nova Scotia are naturally acidic over most of the province,” Keys says. “Decades of acid rain has probably lowered average pH to some degree, but more importantly it has decreased the supply of base nutrients like calcium, magnesium, and potassium, and increased the concentration of mobile aluminium in many soils, especially in western Nova Scotia. In many sites this can lead to decreases in current or future productivity, especially if exacerbated by poor forest management.”

The way Keys describes it, the bank of nutrients in the province’s soil has been cleaned out. He says forests’ reduced capacity to regenerate after harvesting needs to be incorporated into management practices, and the provincial government is moving in this direction.

In a paper on the NS Forest Nutrient Budget Model published earlier this fall, Keys and co-authors acknowledged that “harvest removals can exacerbate declines in base cation levels (especially Ca) in affected soils”, an admission, perhaps, that clearcutting has some downsides for forest productivity AND aquatic systems. That’s Progress. It can’t get into the forest planning processes soon enough.

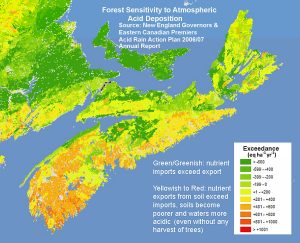

It would make most sense simply to severely restrict if not ban clearcutting in whole watersheds severely stressed by acid rain. We already know which watersheds those are (view figure above). As well as speeding up improvement of water chemistry for salmon and other species, such restrictions would prevent other deleterious effects of clearcutting on salmon habitat. What’s good for trees is also good for salmon!

There is a hitch however. The most severely affected watersheds are in the Western Crown Lands (“the last great wood basket”) that the NS government is handing over to the Westfor group to manage and cut. In fact they are just completing the first year in a planned ten year deal that would see a lot of clearcutting.

From: Miller, E. et al. 2007. Mapping Forest Sensitivity to Atmospheric Acid Deposition. Conference of New England Governors and Eastern Canadian Premiers Forest Mapping Group Report.

The relationship of salmon declines to low calcium in forests was well known well before those agreements were conceived. The broad outlines of the salmon story have been known since the 1980s when declines in salmon on the Atlantic coast of Nova Scotia were related to acidification of surface waters. By the mid-2000’s, it was clear that forest soils over more than 50% of Nova Scotia’s land mass have unusually low buffering capacity in comparison to most other jurisdictions in eastern North America and are critically low in nutrients (notably calcium) essential for the health of both the forests and aquatic systems in many of our forested watersheds

For the sake of the forests and salmon, it’s time for NSDNR/Westfor to heed the science (including their own) and put the brakes on clearcutting in SW Nova Scotia.

More Info

The endangered Southern Upland salmon

- Recovery Potential Assessment for Southern Upland Atlantic Salmon

Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat Maritimes Region Science Advisory Report 2013/009

Southern Upland (SU) Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) was assessed as Endangered by COSEWIC in November 2010. The Southern Upland DU of Atlantic salmon consists of the salmon populations that occupy rivers in a region of Nova Scotia extending from the northeastern mainland near Canso, into the Bay of Fundy at Cape Split…Based on genetic evidence, regional geography and differences in life history characteristics SU Atlantic salmon is considered to be biologically unique (Gibson et al. 2011) and its extirpation would constitute an irreplaceable loss of Atlantic salmon biodiversity.

Liming trials in Nova Scotia (the first in North America)

- Restoring Salmon Rivers with Liming

FLYLIFE MAGAZINE, MAR. 19, 2013 reposted on Atlantic Salmon Federation website. Quick summary of the why, what and how of the lime doser on the West River. - Initial Results of an Atlantic Salmon River Acid Mitigation Program

E.A. Halfyard, 2008. MSc thesis, Acadia University. The thesis provides photos and details of lime doser on The West River, Sheet Harbour and results of early monitoring. - Terrestrial liming to promote Atlantic Salmon recovery in Nova Scotia – approaches needed and knowledge gained after a trial application.

S. M. Sterling et al. 2014 Hydrology and Earth System Sciences 11, 10117–10156. ” The lakes and streams of SWNS were among the most heavily acidified in North America during the last century and calcium levels are predicted to continue to fall in coming decades. One of the most promising mitigation options to reduce the risk of extirpation

of the SWNS Salmo salar is terrestrial liming; however, both the chemistry of SWNS rivers, and effective strategies for terrestrial liming in SWNS are poorly understood. Here we have launched the first terrestrial liming study in Nova Scotia” - What is the dosage of powdered limestone needed to raise water quality to within target levels in southwestern Nova Scotia? Honours thesis by Jillian Haynes, Department Of Earth Sciences, Dalhousie University, 2016. (Supervisor: Shannon Sterling)

The thesis includes data collected after that reported in the paper above, also a lot of background info. about terrestrial liming. - Wild Atlantic salmon project ‘biggest ever’ in Eastern Canada

Program uses helicopters to add lime to soil in effort to improve habitat along West River Sheet Harbour

CBC report Oct 31, 2016 - Groups use lime to help restore salmon to river

CH September 16, 2015. No longer available

Linkage of aquatic acidification and forest soils in Nova Scotia

- See Calcium Depletion on this website.