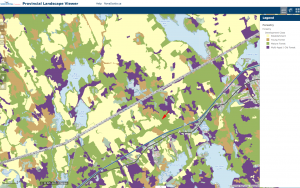

Can we heal our landscape AND maintain wood supply as in the recent past or even grow the supply as contended by L&F/Minister Rankin? Where will the High production Forestry sites be placed in this landscape? The image is a screen capture from the NS Provincial Landscape Viewer (Nov 19, 2019) – the pale yellow is forest recovering from clearcuts. What remains of multi-aged/Old Forest (purple) is severely fragmented. From NSFN post post: “So many clearcuts” in SW Nova Scotia (continued) 20Nov2019

As Addie and Fred Campaingne pointed out, the fundamental principle underlying the Lahey recommendations is to redress the balance between commercial uses of forests and protecting ecosystems and biodiversity.

“In other words, I have concluded that protecting ecosystems and biodiversity should not be balanced against other objectives and values as if they were of equal weight or importance to those other objectives or values. Instead, protecting and enhancing ecosystems should be the objective (the outcome) of how we balance environmental, social, and economic objectives and values in practising forestry in Nova Scotia.” – William Lahey, Aug 2018

It looked for a brief moment in early Sepember of 2018 that L&F took this seriously, sending out in a directive to its industrial partners a set of precautionary measures that would have immediate negative impact on harvesting for the benefit of biodiversity. That lasted barely a week before it was retracted. On Oct 1, 2018, coincidentally or not the day the “new NAFTA” was agreed upon in principle, the province secretly signed a one year deal with Westfor that removed restrictions that had been applied when the Independent Review was announced (before the provincial election); the Report of the Independent Review was in (Aug 21, 2018) but not responded to by government, so logically the restrictions should have continued. There followed that fall and over the winter, a rash of harvesting and proposed or actual harvesting of old growth stands that created and is still causing widespread upset and public protest – just read the posts on this website from Nov 2018 to June 2019 and the Social Media Posts that began on Jan 16, 2019. To me, the epitome of L&F’s Forestry First priority and downplaying of biodiversity concerns is the continuing fiasco over the Dalhousie-Corbett Lakes forest.

More definitive evidence of the Forestry First priority came when L&F/Minister Rankin finally issued an initial response to the Lahey Recommendations, on Dec 3, 2018. Minister Rankin made it very clear that they did not accept the perspective of Lahey and Co. on the effects of implementing their recommendations on wood supply. From the Lahey Report (bolding mine):

64. The Review team estimates that this represents a short‐term reduction in wood harvest from Crown land of approximately 10–20 per cent, with the loss being distributed unevenly across regions, depending primarily on the character of the forests on Crown land from region to region. Greater harvesting from sites of high‐production forestry on Crown lands is not a short‐term option for addressing this reduction in wood from Crown lands; harvests from those areas are already included in the wood supply model that shows a 10– 20 per cent reduction in wood from Crown lands due to implementation of the revised EBM system. Similarly, higher harvesting from private‐land plantations is also not an option in the short term: they are already projected in the wood supply model to be harvested as well. This leaves increased harvesting on other private land, including woodlots, where the proportion of harvesting by clearcutting is already over 80 per cent. Nova Scotia’s sustainable harvest level, which is above actual harvest, suggests the trees are there. The issue will be whether they are available to industry on economic terms. – From the Lahey Report, p 29

No, said Minister Rankin he disagreed, stating “We believe that we can sustainably grow this industry.” (CBC Dec 3, 2018). He provided no documentation to back up his statement. There would be less clearcutting, but not less harvesting.

Incredulously and most revealingly, even after NP closed The Mill (or mothballed it, they apparently still believe they will eventually get a pipe), and the market had largely collapsed, the Minister insisted that there would be no let up in Crown land harvests.

“At this time it wouldn’t be appropriate to start scaling back the supply of our sawmills,” Iain Rankin told reporters after a cabinet meeting on Thursday.

Rankin said sawmills around the province still need fibre to make products and the process his department uses for assessments and approvals for harvesting has not changed. – CBC Feb 1, 2020

More recently, Minister Rankin provided a new twist to his rationale for not reducing harvesting on Crown lands:

“It’s not really the time to tell sawmills that they would be reduced in supply, especially given some of the private woodlot supply — we have private woodlot owners that are not selling. So [mills] require that Crown fibre.” CBC Mar 11, 2020

Ouch. Let’s hope the new NAFTA folks in the U.S. don’t notice that one. Commented practicing forester AF on social media: “Lucky for the mills dnr [L&F] is handing out wood in a collapsing market.. how will private land owners ever see a fair price for their wood with crown handing it to Westfor?

That comment seems to answer one question I have long had: “why is Big Forestry, apparently, so dependent on Crown lands when we are told it accounts for only 20% of the supply ?” I say “apparently” because Big Forestry is so vocal whenever it appears that the wood supply from Crown lands is threatened. (This reaction is not recent, re: the hiring of Robert Wagner in 2010 to trash the Bancroft and Crossland Report following the Natural Resources Strategy recommendations to reduce clearcutting). So, apparently, that’s because it’s cheaper and they can use their guaranteed supply from Crown land to negotiate down private woodlots. At least that’s how it appears. (I would be very pleased to post a counter perspective on NSFN.)

Another question I had when I set out on June 21, 2016, to “understand forests and forestry” in Nova Scotia was “Why are the big sawmills so defensive about clearcutting when it seems clear that in the long run, it will result in a reduced supply of high quality, large diameter trees?”

The conclusion I come to was that, given there are still some sizeable chunks of forest stands significantly older than 40-60 years, notably in SW Nova Scotia, clearcutting can still provide larger diameter logs to sawmills and do it at lower expense than selective cutting (at least as long as there is a market for the smaller stuff) and it is the current bottom line that reigns supreme in our industrialized society; technology will take care of the future, e.g. by manufacture of synthetic woods not dependent on large diameter logs.

That may be true as a first approximation, but Linda Pannozzo provided a much more nuanced explanation to do with improvement in the efficiency of sawmills concurrent with falling diameters of logs, and a shift in the production of chips from the pulp mills to the sawmills. View: Pulp Culture: How Nova Scotia’s Faustian bargain with the pulp industry may leave the sawmills in ruins in the Halifax Examiner, Mar 12, 2020.

And the future technology I referred to is already here. From the Canadian CLT Handbook 2019 Edition Volume 1, page 4 (bolding mine):

1.3 DEFINITION OF CROSS-LAMINATED TIMBER

Cross-laminated timber (CLT) panels consist of several layers of lumber boards stacked crosswise (typically at 90 degrees) and glued together on their wide faces and, sometimes, on the narrow faces as well. Besides gluing, nails, screws, or wooden dowels can be used to attach the layers. Innovative CLT products such as Interlocking Cross-Laminated Timber (ICLT) are in the process of development in some countries. However, non-glued CLT products and systems are out of the scope of this Handbook. A cross-section of a CLT element has at least three glued layers of boards placed in orthogonally alternating orientation to the neighbouring layers. In special configurations, consecutive layers may be placed in the same direction, giving a double layer (e.g., double longitudinal layers at the outer faces and/or additional double layers at the core of the panel) to obtain specific structural capacities. CLT products are usually fabricated with an odd number of layers; three to seven layers is common, even more in some cases. The thickness of individual lumber pieces may vary from 16 mm to 51 mm (5/8 in to 2.0 in) and the width may vary from about 60 mm to 240 mm (2.4 in to 9.5 in). Boards are finger-jointed using adhesives meeting severe durability requirements. Lumber is visually graded or machine stress rated and is kiln-dried.

So the sawmills don’t need big trees anymore to make big lumber. It’s as simple as that. So it’s no surprise that the diameter objectives for softwoods envisaged for High Production Forestry are 8-12 inches, dependent on species. From the High Production Forestry Phase 1 – Discussion Paper:

As one of the key objectives of the High Production Forest zone is to grow an abundance of saw material products (i.e saw timber, or sawables), each of the species growth and yields have been modelled with this as the focus. Red spruce plantations have been modelled to achieve an average diameter of 12” (30cm), with a focus on maximizing sawlog volumes from a piece size which is efficient for sawmills to utilize. White spruce plantations have been modelled to achieve an average diameter of 10” (26cm), with a focus on maximizing both sawlog and studwood volumes from a piece size which is efficient for either stud mills or sawmills to utilize. Norway spruce has market limitations and cannot be utilized for sawlogs, therefore Norway spruce plantations have been modelled to achieve an average diameter of 8” (20cm), with a focus on maximizing studwood volumes from a piece size which is efficient for stud mills to utilize.

All well and good, but as L&F works the numbers* to come up with its sustained wood supply, there will not be much incentive from a forestry perspective to grow big (>20″) old (>100 yrs) trees and old forest in the Ecological Matrix component of the Triad. And there will be lots of benefit from selecting existing older high volume stands as HPF sites, and harvesting them as they wait for younger sites to reach that 8-12″ – but not in regrowing them.

________________

*From the High Production Forestry Phase 1 – Discussion Paper: “In addition to the analyses detailed in this discussion paper, the HPF team plans to complete a strategic, long-term wood supply analysis as part of Phase 1 of this project which will use the Crown Lands Forest Model (CLFM) to explore impacts of zoning varying amounts of total HPF area on Crown lands (e.g. 5%, 10%, 15%, 18%). Also included in this analysis will be the impact of ecosystem-based management (EBM) targets. This analysis, which will be a part of the Phase 1 final report, will allow the trade-offs of varying HPF area to be quantified when selecting the total area allocated to HPF in Phase 2. Input will be gathered from various stakeholders, the general public, L&F staff, and external experts through stakeholder engagement which will be used to finalize the Phase 1 report, detailing the methods and strategy used to identify potential HPF sites, along with potential wood supply and EBM target impacts of HPF. The final report will serve as the baseline for Phase 2 of the project, which involves site selection and classification of HPF on the landscape.”

And let’s not forget about the efforts to bring a biorefinery to NS, which could operate on rotations even shorter than those required to produce trees of 8-12″ and require a plentiful supply to remain competitive.

For these reasons, we need a Biodiversity Landscape Plan, even a precautionary one, to protect a minimum of Old Forest and other key biodiversity values before selecting the HPF sites- and before L&F works the numbers on wood supply once again.

——–

Some related posts & links

Why we need a Precautionary Biodiversity Landscape Plan for Nova Scotia 16Mar2020

Post on NSFN Mar 16, 2020

– L&F looking for Resource Specialist for the Crown land IRM planning process and wood supply forecasts 2Apr2019

Post on NSFN Apr 2, 2019

– Clearcut Nova Scotia continued..17July2017 & how much wood can be harvested from one hectare

Post on NSFN Jul 17, 2017

– Biodiverse Southwest Nova Scotia at Risk

Post on NSFN Oct 29, 2018

– As Mass Timber Takes Off, How Green Is This New Building Material?

BY JIM ROBBINS • APRIL 9, 2019 for Yale Environment 360. “Mass timber construction is on the rise, with advocates saying it could revolutionize the building industry and be part of a climate change solution. But some are questioning whether the logging and manufacturing required to produce the new material outweigh any benefits…The forestry part is what has some skeptical of how ecologically sound mass timber is and, if and when it’s scaled up, whether it will truly provide a planetary climate solution. In a letter to the city of Portland last year, representatives of Oregon environmental groups — including the Audubon Society, the Sierra Club, and Oregon Physicians for Social Responsibility — raised serious doubts about mass timber as a green climate solution and questioned the city’s plan to use it. First and foremost, they said, is the need to certify that wood is logged sustainably and certified as such. “Without such a requirement,” the letter stated, the city “may be encouraging the already rampant clear-cutting of Oregon’s forests… In fact, because it can utilize smaller material than traditional timber construction, it [mass timber] may provide a perverse incentive to shorten logging rotations and more aggressively clear-cut.” Such industrial-type forestry — large-scale plantings of trees selected to grow fast — creates a “biological desert,” said Talberth, of the Center for Sustainable Economy. “And it’s driving the extinction of thousands of species. Mass timber is mass extinction.” “We must ensure that mass timber drives sustainable forestry management, otherwise all of these benefits are lost,” agreed Mark Wishnie, director of forestry and wood products at The Nature Conservancy. “To really understand the potential impact of the increased use of mass timber on climate we need to conduct a much more detailed set of analyses.”