Page created June 8, 2022 at nsforestnotes.ca/Consultations/News & Comments

- SUMMARY

- Deforestation’ versus ‘Forest Degradation’

- We can no longer ignore effects of “forest degradation”

- Current Landscape level goals for Old Forest conservation

- Forest degradation in Nova Scotia: Highgrading at the Landscape Level

- How much Old Forest do we need?

- & What about the wood supply?

- Conclusion: can Nova Scotia be a model for the practice of Triad Forestry?

1. SUMMARY

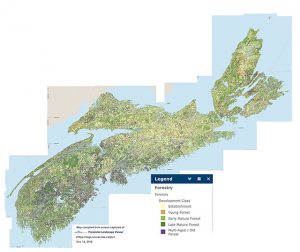

Distribution of forest in 5 development stages across Nova Scotia, compiled from NS Landscape Map Viewer in 2018. Purple = Multi-aged/Old Forest. Dark Green=Late Mature Forest. Click on image for larger version. View larger versions of the map: 2000 px | 4000 px.

The dark green and purple patches correspond, more or less, to ‘Old Forest’ – forest 80+ years old. Today it is most concentrated in SW Nova Scotia where there is a high proportion of Crown land and where a consortium of mills (“WestFor”) is harvesting these older forests.

Big Forestry in Nova Scotia, the forestry folks in the Nova Scotia government and the federal forestry folks in Canada like to point out that there has been very little deforestation in Nova Scotia and in Canada at large, and consequently that “Canadian forests are healthy, productive and thriving.”

Critics have maintained that while the forest cover may not have changed much, forest degradation has occurred though conversion of older forest to younger forest and though species simplification, resulting in reduced carbon storage, and losses in biodiversity.

Forest degradation, defined as ‘the human-induced loss of carbon stocks within forest land that remains forest land’ is addressed in international agreements to which Canada is a signatory and in principle is accounted for by changes in carbon stocks (essentially wood volumes). The forest industry and many governments including the feds contend that such losses are not the same as deforestation because ‘the forest grows back’, and so deflect attention to deforestation, especially in tropics where there is a lot of deforestation. Further, the existing system of carbon accounting obscures the specific gains and losses associated with logging by ‘throwing it all in one basket’.

Industry and government have been able to largely ignore the effects of forest degradation defined more broadly as loss of ecosystem services because except for carbon storage, ecosystem services are not so readily measured.

That changed with the The ‘2022 bird study’; it illustrates conclusively that forest degradation in the Maritme Canada region in the form of loss of Old Forest, not just loss of Old Growth forest, has led to large declines in bird populations across many species. (For NS, Old forest is forest 80 and more years of age & Old growth, 125 and more years of age.)

In Nova Scotia, such losses continue today primarily via ‘high grading at the landscape level’: the harvest of remaining patches or stands of old trees/older development stages in landscapes where there has been extensive clearcutting over the last 30-40 years.

Current Landscape Level goals for Old Forest conservation in NS are limited to protection of Old Growth and some 0lder forest, the latter mostly in existing protected areas. Protection of Old Growth (forests 125 years and older) is not controversial because there is such a small amount (0.3% or less by area), that its protection has essentially no impact on wood supply from Crown lands.

The Old Forest Policy protects approximately 10 % of Crown lands, most of it as potential Old Growth, and most of it is in existing protected lands so it is not sought by sawmills; about half of the land so protected is Old Forest currently; but because Crown lands are only about 1/3 of forested land, the Old Forest Policy protects less than 3% of the forest land in NS as Old Forest compared to perhaps 15% in total.

We urgently require a Precautionary Landscape Level Plan for Old Forest conservation. An example of how that might look is suggested based on the recommendation of Mosseler et al. 2003 that at least 20–25% of our forest be maintained in late-successional forest types.

The Triad system that NS is currently putting in place for management of Crown lands is intended to minimize the tradeoffs involved in managing forests to serve the need for both extraction of wood, and to maintain the forests’ multiple, non-extractive values (“Ecological Services”).

The Triad is “inherently landscape-oriented and intentionally planned” (Hines et al, 2022); that landscape level planning is the piece is still lacking in Nova Scotia.

It’s important to recognize that the Triad is not a proven system but a concept and now a few experiments in which there is widespread interest. Its application in NS is the biggest trial of it yet. Many people and institutions outside of NS will be watching how it unfolds and very likely conducting rigorous independent assessments of how well it works socially and in regard to achieving the desired balance between wood production and ecological services.

The current government has committed to full implementation of the Triad by 2023. Just how it unfolds and in particular how current Old Forest is assigned to each of the 3 components of the Triad and how much wood is harvested in successive years will determine whether Old Forest cover in NS continues to decline, remains at current levels, or, as we need in order to reverse losses in biodiversity, increases.

2. Deforestation versus Forest Degradation

Big Forestry in Nova Scotia, the forestry folks in the Nova Scotia government (now residing in NSNRR) and the federal forestry folks in Canada like to point out that there has been very little deforestation in NS and in Canada at large.* This, the feds say, is evidence enough that “Canadian forests are healthy, productive and thriving.”

Critics have maintained that while the forest cover may not have changed, forest degradation has occurred though conversion of older forest to younger forest and though species simplification, e.g., see NRDC, 2017

__________________

*Deforestation occurs when forest is converted to an unforested state (NG) e.g., it’s cleared for settlement or agriculture. “Afforestation” is the establishment of a forest or stand of trees (forestation) in an area where there was no previous tree cover.(WP) In NS, overall, we have had net afforestation since the early 1900s due to abandonment of agricultural lands and their natural reversion to forest, but net deforestation of about 15% of the land since pre-settler times. (See Land Base). Forest Degradation is variously defined. The UN-REDD (United Nations Programme on Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation) defines it as ‘ the human-induced loss of carbon stocks within forest land that remains forest land’* .Thomson et al., 2013 define it as “reduction in the capacity of a forest to produce ecosystem services; Betts et al., 2022 define is as “the reduction or or loss of biological complexity in forests”, e.g.by changing the age structure through clearcutting or highgrading (selective removal of oldest trees), use of herbicides to increase softwoods.

*UN-REDD Technical Resource Series 3: Towards a Common Understanding of REDD+ under the UNFCCC (2016)

But look for the term ”forest degradation” on NS and federal websites, it’s hard to find. The government foresters don’t talk about it, instead repeat the no-deforestation mantra.

Forest degradation, defined as ‘the human-induced loss of carbon stocks within forest land that remains forest land’ is addressed in international agreements to which Canada is a signatory and in principle is accounted for by changes in carbon stocks (essentially wood volumes). The forest industry and many governments including the feds contend that such losses are not the same as deforestation because ‘the forest grows back’, and so deflect attention to deforestation, especially in tropics where there is a lot of deforestation.

Forest degradation, defined as ‘the human-induced loss of carbon stocks within forest land that remains forest land’ is addressed in international agreements to which Canada is a signatory and in principle is accounted for by changes in carbon stocks (essentially wood volumes). The forest industry and many governments including the feds contend that such losses are not the same as deforestation because ‘the forest grows back’, and so deflect attention to deforestation, especially in tropics where there is a lot of deforestation.

More misleading, the actual changes in carbon stocks due to forest management are obscured by including within the managed areas, large areas that are not harvested (and in which carbon stocks are increasing). This accounting is controversial, and perhaps arguable both ways, but increasingly is being called out*. However for the time being, the ‘forests grow back’ argument, and the existing accounting systems have enabled Big Forestry and the Canadian government (which does the accounting for NS) to avoid admitting that forest degradation is a major issues in Canada.

_____________

*See, e.g., Canada’s approach to forest carbon quantification and accounting: key concerns

Nature Canada document by MJ Bramley 2021; Estimating carbon stocks and stock changes in Interior Wetbelt forests of British Columbia, Canada y D.A. DellaSala et al., 2022 in Ecosphere; Net carbon accounting and reporting are a barrier to understanding the mitigation value of forest protection in developed countries by Brendan Mackey et al., 2022, 2022 Environ. Res. Lett. 17 054028.

In addition, forestry folks in government have been able to largely ignore the effects forest degradation defined more broadly as loss of ecosystem services* because except for carbon storage, these are not so readily measured ( Thomson et al., 2013).

While there has been strong suspicion that forest degradation is a cause of declines in biodiversity – a major driver of ecosystem services* – clear stats on both biodiversity declines and any connection to changes in the forests have been lacking. Thus in response to concerns that forestry practices were contributing to bird declines, NSDNR responded:

“Bird populations and habitat are impacted by many human activities on the landscape and forestry is not among the most significant source of impacts” compared to cat predation, housing and road development, and vehicle collisions.” -View NSFN Post June 8, 2018

________________

*”Ecosystem services are the benefits people obtain from ecosystems. These include provisioning services such as food, water, timber, and fiber; regulating services that affect climate, floods, disease, wastes, and water quality; cultural services that provide recreational, aesthetic, and spiritual benefits; and supporting services such as soil formation, photosynthesis, and nutrient cycling”. …The Millennium Assessment recognizes that interactions exist between people, biodiversity, and ecosystems. That is, changing human conditions drive, both directly and indirectly, changes in biodiversity, changes in ecosystems, and ultimately changes in the services ecosystems provide. Thus biodiversity and human wellbeing are inextricably linked.- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment

Likewise, NSDNR denied that forestry practices had contributed to simplification of our forests through the process of “borealization”. (NSFN Post Nov 3, 2017)

3. We can no longer ignore effects of “forest degradation” on forest biodiversity

Blackburnian Warbler

Photo by William H. Majoros, on Wikipedia

The lack of clear evidence linking biodiversity declines to forest degradation changed with the publication of Forest degradation drives widespread avian habitat and population declines by MG Betts et al., 2022. This “2022 Bird Study” (my shorthand for it), published in a top scientific journal and headed by Matt Betts, a prof at Oregon State University and a New Brunswicker by birth, was based on data for the Maritime Provinces.

In a nutshell, this is what it showed:

Overall, our results indicate that forest degradation has led to habitat declines for the majority of forest bird species with negative consequences for bird populations, particularly species associated with older forest. Forest changes include conversion from mixed-species forests to single-species conifer-dominated plantations or thinnings and clear-cutting old forests without equivalent regrowth into old age classes

The authors are well aware of the implications.

If maintaining non-declining populations of forest birds is the goal, conservation measures that halt the alteration of habitat, particularly in diverse, older forests, will be necessary.

Of course, this may come at the expense of wood production but potentially less so with forest-landscape zoning that maintains reserves, ecological forestry and spatially limited intensive management.

The full paper is publicly available in Nature, Ecology & Evolution. Some extracts and links to interviews, press reports etc. are available on this website. It’s hard to understate the significance of this paper not just for the Maritimes, but for managed forest landscapes more broadly. Also, while it deals with birds, the patterns observed very apply to forest biodiversity more broadly.

4. Current Landscape level goals for Old Forest conservation in NS are limited to protection of Old Growth (not Old Forests)

This ‘2022 Bird Study’ puts an onus on our NS government, in its quest to implement ecological forestry in NS, to set clear landscape-level goals for Old Forest conservation, i.e. to define how much Old Forest* we want to see on our landscape and where.

The only commitment of this nature that we have in place now in Nova Scotia is to conserve existing Old Growth* forest .

____________

*For Nova Scotia, Old Growth is defined as “A forest stand where 30% or more of the basal area is in trees 125 years or older, at least half of the basal area is composed of climax species, and total crown closure is a minimum of 30%. Old Forest is defined as “Any stand or collection of stands containing old growth and/or mature climax conditions” and Mature Climax as “A forest stand where 30% or more of the oldest basal area is in trees 80 – 125 years old, at least half of the basal area is composed of climax species, and total crown closure is a minimum of 30%.” (Source: Nova Scotia’s Old Forest Policy, 2012). So essentially, Old Growth in Nova Scotia is forest 125 years and older; Old Forest is forest 80 years of age and older.

In British Columbia where there is still a significant amount of Old Growth (somewhere in the range 5-15% of forested area; 50% or more 100 years ago) and it is still being logged, there have been mass protests and blockades over the logging; now that the government has moved to at least slow down the cutting of Old Growth, the forest industry is also up in arms. (Browse Treefrog Forestry News for related news).

We generally don’t have battles over Old Growth in NS because there is so little genuine Old Growth left, circa 0.3% or less by area,* that protecting it – which we do, at least for larger patches – is not a threat to the forest industry.

*This is the number generally cited but NRR seems adverse to releasing an official number saying only that it is rare

However we have had our ‘forestry battles’ and they continue today. Earlier battles were focussed on clearcutting; it was the major issue of concern to both the forestry review under the Natural Resources Strategy (2008- 2010), and the Independent review of Forest Practices (aka the Lahey Report, or Forest Practices Review, FPR, 2017-2018).

Subsequent to the Lahey Report of 2018, the focus has increasingly shifted from concerns about clearcutting generally, to loss of Old Forests, whether they are being clearcut, or just degraded by partial cuts; I have described this as “high-grading at the landscape level”.

5. Forest degradation in Nova Scotia: Highgrading at the Landscape Level

Forest Degradation in Nova Scotia today is occurring primarily via “High-grading at the Landscape-level”, whether by clearcutting or partial cuts.

“High-grading” is a term applied by foresters at the stand level, and refers “the removal of only the best trees from a stand, often resulting in a poor quality remaining stand and poor seed for the next generation”*

By analogy, high-grading at the landscape level is the selective harvesting of remaining patches or stands of old trees/older development stages in a landscape where there has been extensive clearcutting.

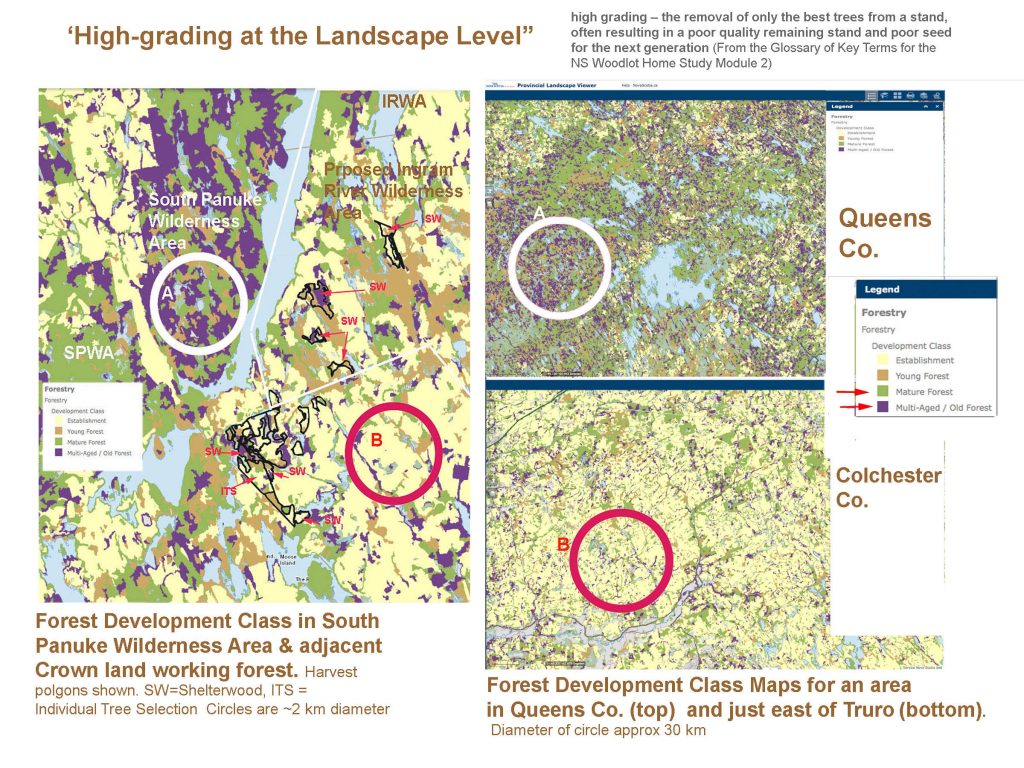

Highgrading at the Landscape Level is readily revealed by examining the Forest Development Class layer on the Nova Scotia Provincial Landscape Viewer.

Examples are shown below. At left, the Forest Development Class in the South Panuke Protect Wilderness Area is dominated by green (Mature Forest) and purple (Multi-aged/Old Forest)’ that contrasts sharply with with adjacent heavily cut, mostly Bowater (now Crown) lands to the southeast which are dominated by yellow (Establishment) and brown (Young Forest). At top right is an area in Queens Co. in SW Nova Scotia where there still remains a lot of older development class forest on the landscape; it contrasts sharply with an area in heavily harvested Colchester Co. in Central Nova Scotia (bottom right).

Also shown in the diagram at left are polygons for planned harvests on Crown lands, mostly Shelterwood cuts; those are focussed on remaining patches of later successional stages.

Appropropriately, recent forestry protests spearheaded by ‘the Women of SW Nova Scotia’/Extinction Rebellion Mi’kma’ki / Nova Scotia, notably at the Corbett lake Old Hardwood Forest (2018-2019) and currently (Dec 1 2021 and ongoing) over AP068499 Beals Meadow have not been about clearcutting, but about harvesting remaining patches of Old Forest in landscapes where there has been pervasive clearcutting.

Sound of Silence at Corbett-Dalhousie Lakes forest. June 15, 2019. The protest was not about clearcuts but about shelterwood harvests that are degrading intact Old Forest (with patches of Old Growth) and hosting several Species-at-Risk and removing the biggest, oldest trees. View Video & Nova Scotia Old Growth Ground Zero. Likewise, the ongoing protest at AP068499 Beals Meadow is about removing the last stands of old forest on a landscape where there has been pervasive clearcutting.

That subtlety has so far not been recognized by the forestry folks NSNRR who insist that because the harvests at The Corbett Lakes forest and at AP068499 Beals Meadow are being conducted ‘according to Lahey’, they are OK.

6. How much Old Forest do we need?

Currently, there is no goal for the amount of Old Forest we should plan for in NS. There is a goal for Old Growth forest, set in Nova Scotia’s Old Forest Policy published in 2012, and retained in the draft Old Growth Forest Policy of 2021, which is 8% of Crown land in each ecodistrict. Those lands have already been designated, and include land in existing protected lands, and Crown land that is currently working forest.

We are starting something less than 0.3 % of existing Old Growth for the province as a whole. Remarkably amongst those designated 8% lands, about half of the forest is under 80 years old – when much more Older Forest (80 years plus) could have been chosen.(See comments by LeDuc, 2018) So little or no consideration is given to speeding up as much as possible the achievement of Old Growth on the 8% of Crown land (i.e. to always priorizing conservation of older forest over younger forest).

As well, in Nova Scotia, Crown land accounts for only about 1/3rd of the forested land. So our 8% commitment currently protects only approximately 8% x 33% x 50% = 1.3% by area of Old Forest for the province as a whole (and something less than 0.3% is Old Growth forest). That is clearly inadequate!

*That number seems excruciating low, corrections welcomed. As the ‘8% quota’ has now been achieved and in some ecodistricts, exceeded, the 8% no. should be higher. However even if were 12%, that would still amount to circa 2% for the province as a whole. It seems we can say that the Old Forest Policy protects at best, 3% by area or less of Old Forest in NS.

In fact there is no scientific justification offered for the 8%-of-Crown-land-in-each-ecodistrict goal.

There is a rationale for achieving a common level in all ecodistricts (see The 8% Lands for details) as that ensures a similar level of conservation across NS and in proportion to the varying ecological conditions. However, there is no evident rationale for the 8% figure itself, and it is certainly too low as a target.

How much land and which land should be protected to ensure adequate conservation of Old Growth Forests? We do have a number: In 2003, foresters (two federal and one provincial) offered a target for the Acadian forest region (N.B., N.S. & P.E.I.) based on landscape level considerations:

…Forest resource inventory data suggest that between 1% (Lynds and LeDuc 1995) and 5% (Anonymous 2002, Fig. 1) of Nova Scotia, and perhaps less than 2– 3% of New Brunswick, exists as forest older than 100 years.

Based on the frequency of stand-replacing or catastrophic natural disturbances such as fire and wind in the AFR [Atlantic Forest Region], the length of time required to develop OG, and the areal distribution of temperate-zone forests in the AFR capable of developing these late-successional forest types, we estimate that 40–50% of the pre-settlement forested landscape may have been occupied by OG forest.

Although the question of how much area should be kept in OG forest types is largely an issue of social and economic policy, given our estimates of the extent of OG in the pre-settlement forest, it seems reasonable to suggest that at least 20–25% of our forest be maintained in these late-successional OG forest types*, perhaps 10–12% within protected areas and 10–12% within the working forest.

– Mosseler et al. 2003.Old-growth forests of the Acadian Forest Region. Environmental Reviews 11: S47–S77.

A target of 25% seems pretty reasonable, even conservative compared to the 40-50% historically. We currently have of the order of 15-20% Old Forest, so we we need to move as quickly as possible to ensure that increases, not decreases or remains the same. So how about this:

Implement a Precautionary Old Forest Protection Plan that requires a minimum 25% of forest to be in the oldest development stages ( Mature and Multi-aged/old forest*) in each ecodistrict, with at least half of that area on Crown lands. If the total for an Ecodistrict that is currently in the oldest development stages is less than 25%, then there should be no logging on those Crown lands.

A benefit of such an approach is that we have already classified and mapped the development stages for all of our forests (see map above) although some updates may be required and obviously should be ongoing.

__________________

*In the process of looking at various screen captures of the Forest Development Stage layer than I have made over the past several years, I discovered that sometime after 2019, the Early Mature and Late Mature categories were collapsed into one category (Mature); it’s not clear whether all of the mature forest so labelled can be considered ‘Old Forest’ (forest 80 years and older). – see Post June 7, 2022

There is a more refined approach developed under the aegis of Natural Disturbance Regime Ecological Forestry project, which involves using the return intervals f0r natural disturbance regimes to infer target stand age-class distributions for different Community Types (MacLean et al., 2021); it was used used to inform development of the Silvicultural Guide for the Ecological Matrix (SGEM). In principle, if it were fully applied, the % of forest in the older development stages would likely eventually be much higher than 25%.

However, it is totally a stand level approach. For example, there is no provision in the SGEM to adjust the size of “reserves” according the amount of Old Forest remaining in the surrounding landscape. and MacLean et al. 2021 comment

One of the main benefits of ecological forestry is the retention or potential restoration of biodiversity and ecosystem integrity, but metrics and quantitative targets for biodiversity and ecosystem integrity need to be proposed and monitored as an integral part of ecological forestry; these biodiversity targets are lacking in Nova Scotia, highlighting a critical information gap..

That is the first statement from the forestry folks at NSNRR (as co-authors of the study) I have seen yet clearly acknowledging that landscape level aspects of Ecological Forestry are critical and have yet to be addressed. (I hope they repeat it in plain English.)

So right now we need a Precautionary Landscape Level Plan for Old Forest Conservation – whether one such as that suggested above or an alternative – but one that can be introduced to address our linked climate and biodiversity crises without delay, while working on a more refined plan. We cannot afford another 13 year delay to begin reversing (not slowing) biodiversity decline associated with loss of old forest in NS.

7. & What about the wood supply?

The Triad system is intended to minimize the tradeoffs inherent in trying to manage forests to serve both the need for continued extraction of wood, and the need to maintain the forests’ multiple, non-extractive values or “Ecological Services”. A recent comprehensive review by Hines et al., 2022 describes the system, the tradeoffs and the status of this system in detail.

It is critical to recognize that the Triad is “inherently landscape-oriented and intentionally planned” (Hines et al, section 3.4) and that landscape level planning is the piece that is still lacking in Nova Scotia. It is presumably in the works, but we know very little in the public domain beyond the initially floated numbers that seemed well out of line with the concept that “areas where ecological forestry would be practised would form a matrix surrounding protected areas and high‐production areas. Their function in the Triad is to provide a substantial degree of ecosystem integrity across the landscape, connectivity between protected areas, and forest products ” (Lahey, p19)

We do know this:

-Both of the authors/founders of the Triad system – Robert Seymour and Malcolm Hunter (both residents of Maine) – were amongst the 7 Expert Advisors (see Addendum, p1) to Prof. Lahey during the Independent Review, and Robert Seymour continued some involvement subsequently.

– Prof. Lahey & Co. anticipated that wood supply would necessarily be reduced 10-20% during a transitional period.

– NS Lands & Forestry Minister RankinRankin disagreed (without presenting any evidence), and no interim measures to reduce harvests were introduced; clearly there was strong resistance within the Department of Lands and Forestry & Government to any reduction of the wood supply from Crown lands. There has been no indication that has changed under the new government.

On the other hand, the reasons to reduce the wood supply from Crown lands have continued to mount:

– Subsequent to completion of the Lahey Report, the world has become much more aware of the dual and linked crises of Climate Warming & Biodiversity Loss, and Canada has made commitments to significant actions to address these crises by 2030.

– The 2022 Bird study illustrates that massive forest biodiversity loss has occurred in NS and that increasing Old Forest cover in NS is critical to slowing down and hopefully reducing forest biodiversity losses

– Studies by aquatic biologists have illustrated that ‘soil depletion’ due to acid rain and made worse by forest harvesting over approx 60% of our landscape is more intransigent than we had thought, i.e. we cannot assume that future productivity of forests will be the same as in the past – once harvested we may lose significant future potential for carbon sequestration as well as the immediate losses of carbon storage from harvesting Old Forest.

These developments suggest that larger reductions in wood supply from Crown lands particularly from the older, high volume forests than anticipated by Lahey & Co. are likely required if we wish to meet our commitments to reverse losses in biodiversity, and mitigate climate change, i.e. to increase the amount of Old Forest.

As well, because kickback from Big Forestry has led to a close to complete taboo on more regulation of forest management on private lands to improve biodiversity conservation (see NSFN Post Mar 25, 2021), that leaves more of the onus for protecting biodiversity on Crown lands. (Approximately 1/3 of forested land in NS is Crown land, 2/3 private; forests cover approx 75% of the landscape, down from circa 91% in pre-settler times.)

The sawmills prefer the larger volume, old forests with larger diameter trees when they can they can get them because harvesting larger volumes per unit area, and sawing larger diameter trees are economically more efficient than harvesting lower volume younger forests with smaller trees – hence the hunger for Old growth in British Columbia, and for Old Forest in NS (as we harvested most of the Old Growth long ago). However, the forest industry at large and in NS is now well prepared technologically to make use of smaller diameter logs (10-12 ” and less) to meet building material needs through the production of ‘engineered’ or ‘mass’ timber. In fact the High Production Forestry Phase 1 – Discussion Paper specifies a need to grow trees to only 8-12 ” diameter.

As one of the key objectives of the High Production Forest zone is to grow an abundance of saw material products (i.e saw timber, or sawables), each of the species growth and yields have been modelled with this as the focus. Red spruce plantations have been modelled to achieve an average diameter of 12” (30cm), with a focus on maximizing sawlog volumes from a piece size which is efficient for sawmills to utilize. White spruce plantations have been modelled to achieve an average diameter of 10” (26cm), with a focus on maximizing both sawlog and studwood volumes from a piece size which is efficient for either stud mills or sawmills to utilize. Norway spruce has market limitations and cannot be utilized for sawlogs, therefore Norway spruce plantations have been modelled to achieve an average diameter of 8” (20cm), with a focus on maximizing studwood volumes from a piece size which is efficient for stud mills to utilize.

So lets get on with it folks, help the industry make that transition and leave as much as possible of the Old Forest on the landscape!

8. Conclusion: can Nova Scotia be a model for the practice of Triad Forestry?

It’s already being touted as such – if not as a model, as a leading experiment, a subtlety perhaps not appreciated by the Ministers and other politicians who seem to assume that ‘implantation of Lahey’ is all that we need to do, that it’s a proven deal.

It’s not. A recent review describes what’s known about the Triad, and what isn’t, its limitations and challenges.

Perspectives: Thirty years of triad forestry, a critical clarification of theory and recommendations for implementation and testing

Austin Himes, Matthew Betts, Christian Messier, Robert Seymour* in Forest Ecology and Management Volume 510, 15 April 2022. Open Access (full article publicly available).

_______________

*Hines is a forest ecosystem ecologist at Mississippi State, Matthew Betts is the lead author of the “2022 Bird Study”. Robert Seymour is one of the two pioneers of the system; he was an expert Adviser the Independent Review and has some ongoing involvement with NSNRR. Christian Messier is a well published academic in Quebec where the Triad has been in place on a piece of Crown land since the mid 2000s.

From the abstract:

We review the sociohistorical and academic context for triad forest management and related concepts. We argue that the triad has the potential to minimize trade-offs between meeting global demand for timber products and forest ecosystem services.

The triad should include intensive monitoring of multiple ecosystem services outcomes from each of the three management types so that specific practices and allocation between intensive plantations, reserves and the matrix can be adapted to changing societal and ecological conditions.

The triad is an auspicious landscape approach, but to date there is very little empirical evidence supporting triad over alternatives, thus experimental and observation studies are needed to compare the efficacy cacy of the triad over other forest landscape management schemes.

On the current application the Triad, Hines et al 2022 state

Triad is now the basis of forest management in Quebec (Tittler et al., 2016), was recently adopted for implementation in Nova Scotia (Lahey, 2018) and has been proposed as the central theme for the Elliott State Research Forest in Oregon, USA, which will be one of the largest experimental research forests in the world (Tollefson, 2021).

In a 2020 article Austin Hines comments

“Just this year, Nova Scotia has begun the largest scale implementation of the triad approach in a plan for managing approximately 1.8 million hectares of provincial forests.

Wow. So we are right up there, on the leading edge of it all. But that also means, it is not just about NS, and this experiment will be given a lot of attention beyond NS by professional foresters and ecologists, policy makers and in the more public domain. It will very likely be subject to critical, independent assessments of what it achieves in practice, and how those outcomes have been influenced by the decisions made along the way.

So can we succeed?

For a start, I suggest we take a lead from the processes that resulted in the SGEM being a document that has gained wide acceptance amongst the different constituencies in NS: a lot of consultation, independent review by a professional outside of NS, adoption of most or all of the recommendations, and pretty well, full transparency along the way.

There has been some consultation to date on the HPF component of the Triad, and on the Old Growth Forest Policy, but no independent outside review (if there has been, it has not been transparent). There remains some heavy fog around the critical landscape level decisions, particularly in regard to

- how much land and how much of existing Old Forest there will be in each of the HPF and EM components of the Triad and in new Protected lands;

- how much of that existing Old forest will be the chopping block over successive years at least 30 years into the future

The answers will determine whether Old Forest cover in NS continues to decline, remains stable at current levels or increases (as we need to reverse losses in Biodiversity).

To date, we still know next to nothing about another critical component: the Environmental Assessment Process. It is critical because from what we know from the minimal information available about it currently, it is the component that is to provide the main venue for public input going forward. How that is dealt with will have a big influence on public trust and ‘buy-in’ to the Triad.

Hines et al. comment that “The triad should include intensive monitoring of multiple ecosystem services outcomes from each of the three management types”. How this is done is critical. NRR should seek the advice of people like Matt Betts in designing a comprehensive monitoring program. It would likely require involvement of citizen science collected data as in the 2022 Bird Study, open access data, and involvement of professionals outside of the NSDNRR*

It’s important to recognize that the Triad is not a proven system but a concept and now a few experiments in which there is widespread interest. Its application NS is the biggest trial of it yet, and many people and institutions outside of NS will be watching how it unfolds and very likely conducting rigorous independent assessments of how well it works socially and in regard to achieving the desired balance between wood production and ecological services.

“In other words, I have concluded that protecting ecosystems and biodiversity should not be balanced against other objectives and values as if they were of equal weight or importance to those other objectives or values. Instead, protecting and enhancing ecosystems should be the objective (the outcome) of how we balance environmental, social, and economic objectives and values in practising forestry in Nova Scotia.”